"America’s Reichstag fire"

Political violence remains rare, but leaders can help prevent tragedy by condemning hate and defending democratic values

Political violence is an avoidable tragedy that tears nations apart.

The assassination of right-wing activist Charlie Kirk this Wednesday, Sept. 10, 2025, is the latest in a devastating pattern of attacks that rips at the very fabric of American civic life and the Constitution. The recent escalation is stark. Select events from just this year include: the stalking and assassination of Minnesota House Speaker Melissa Hortman and her husband in June, the bombing of a Palm Springs fertility clinic in May, and the attempted murder by arson of Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro and his family in April.

This recent violence builds on years of noteworthy attacks, including multiple assassination attempts against Donald Trump in 2024, the assault of Paul Pelosi and attempted kidnapping of Nancy Pelosi in 2022, and, of course, the events of Jan. 6, 2021, that injured 174 police officers and led to five officer deaths.

To state the obvious: This is not how political disagreements are settled in a functioning democracy.

Details of Kirk's assassination are still emerging. Of particular note is that as of Friday morning, Sept. 12, the shooter remains unidentified and at large. But having written about mass opinion on polarization and political violence for this newsletter in the past, I feel I have something to add to the discourse on his murder.

There is a puzzle at the heart of this recent violence: Most Americans reject political violence in all circumstances, especially when you measure it carefully. The few who do support violence are typically isolated, sick, and, unfortunately, in America, also have easy access to weapons manufactured for the sole purpose of murdering people.

So if support for violence is very low, why does violence appear to be getting more common — and more severe? I’ve taken a look at the evidence from social science, and much of the answer has to do with toxic rhetoric from our political leaders. Rising level of hate and affective polarization, exacerbated by social media, also play a role.

The answers in this piece suggest positive strategies that leaders can take in the aftermath of violent events to reduce the likelihood of future violence. As a consequence of that, they also suggest the current strategy from right-leaning influencers and politicians, including President Donald Trump, is dangerous and counterintuitive.

Very few Americans support political violence

Analyses of Kirk’s killing mostly point to rising societal levels of support for political violence as the culprit (Note: We do not know the identity, ideology, or motives of the man who killed Kirk). In the New York Times, political scientist Robert Pape says we are in a “tinderbox” for violence, with “more radicalized politics and more support for violence than at any point since we’ve been doing these studies in the past four years.”

Pape says that in a March 2025 survey, “nearly 39 percent of Democrats agreed with the idea that removing Mr. Trump from office by force was justifiable. At the same time, nearly a quarter of Republicans said it was justifiable for Mr. Trump to use the military to crack down on protests against his agenda.”

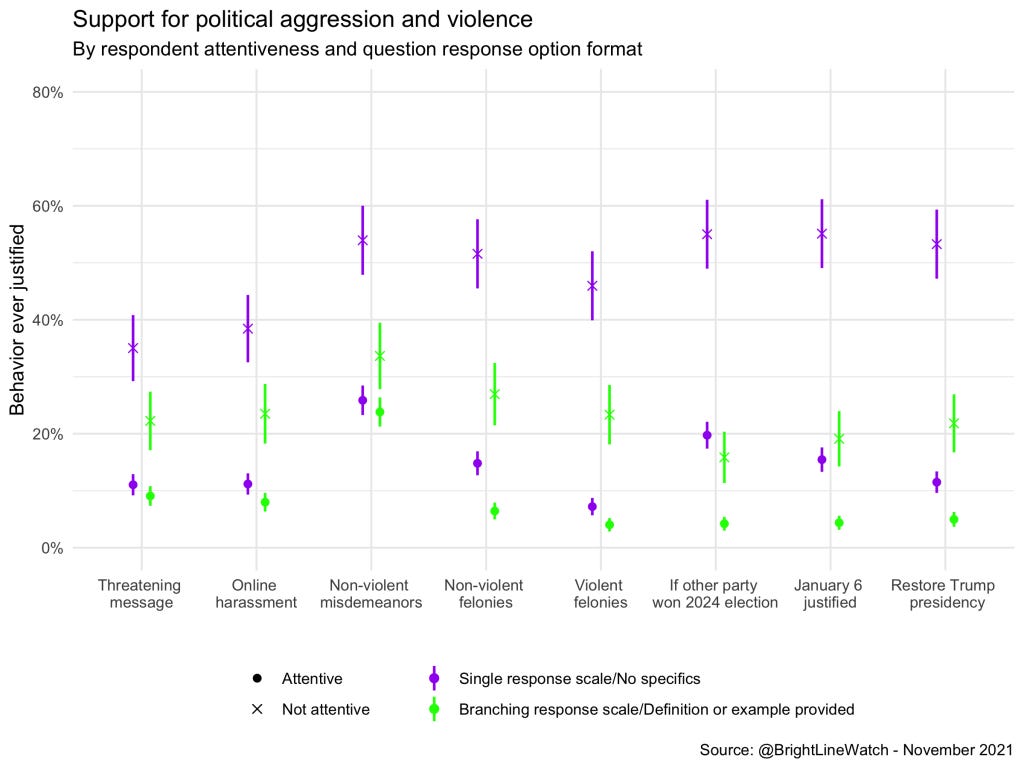

But these questions are not the same as asking Americans if they would use or support specific acts of violence against other people. As a result, they dramatically overestimate the share of the population that would be violent or support violence against the opposition party. A study by Bright Line Watch in 2021 is my preferred citation for the presence of political violence in American politics. This is because the researchers ask about support for specific violent actions, not violence in general, and make sure that their respondents are actually paying attention to and thinking about the question.

When researchers correct these common survey design problems, public support for violence drops sharply. Adding a clear definition and filtering out inattentive respondents yields 9% support for threats, 8% for harassment, 6% for non‑violent felonies, and roughly 4% for violent felonies or using violence if the other party wins:

These levels are far below other headline figures about political violence, which often take online survey respondents at their word or use soft question language that results in higher rates of support.

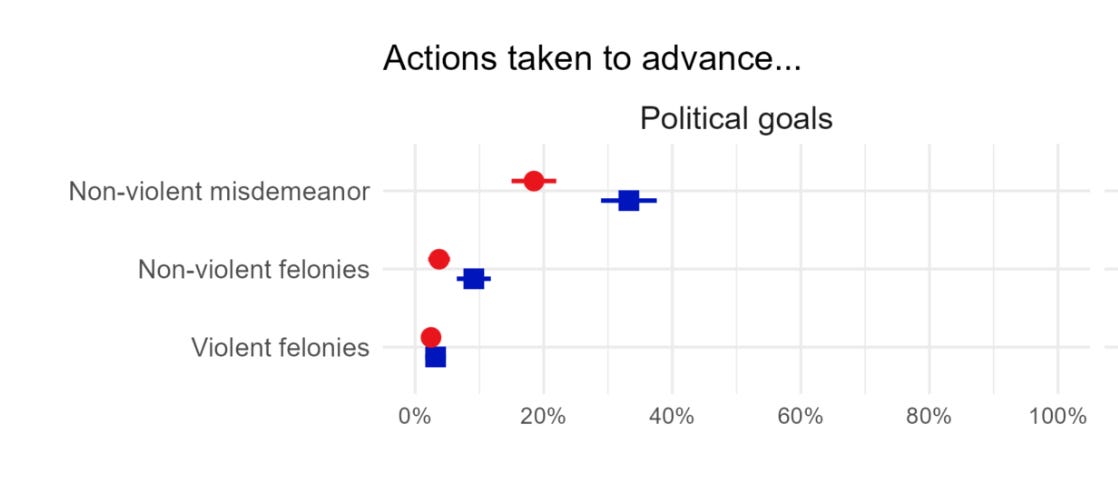

Support for felony violence to accomplish political goals has remained low in future work by Bright Line Watch, including in 2025. Researchers find statistically insignificant difference in willingness to commit violence by political party:

Additionally, The Bright Line Watch’s results are consistent with other studies showing that random responding by disengaged people inflated prior estimates of support for political violence.

Newer studies have also established that the recent apparent increase in violent acts is not reflective of a broader increase in toleration of violence among the public. Here’s a paper published in January 2025 by Wintemute et al. showing no change from 2022 to 2024 in the share of the public agreeing with the statement “Because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence to save our country.” And that percentage was itself low, at just 8% (again, generic questions about violence overstate willingness to actually commit violence).

The bottom line is this: the problem of political violence is real, but smaller than the scariest numbers suggest. Somewhere between 1-in-20 and 1-in-30 Americans support the use of political violence to accomplish political goals.

Of course, that’s still a scary fraction. Even a small share of people endorsing violence is too much. It only takes one out of millions to commit a terrible act of violence. So what can be done about that small, but intensely interested and violent faction actually engaging in violence?

Support for violence partly depends on elite rhetoric

If only a small fraction of Americans genuinely support political violence, why does it keep happening? The answer lies in understanding how that small minority responds to signals from political leaders and influencers.

The evidence from academic literature suggests that one of the biggest factors in the probability of political violence is elite rhetoric. In a new paper, Korean computational social scientist Taegyoon Kim finds that exposure to violent/threatening language from one’s own party’s elites increased support for political violence. The same language from the out‑party elites did not influence views on violence.

So if support for violence is limited and malleable, then elite cues are critical to avoiding future political murders.

Research also finds that violent metaphors polarize voters and raise support among high-aggression followers. One classic experiment from political scientist Nathan Kalmoe demonstrated that even commonplace "fight/war" metaphors can amplify pro-violence attitudes among those high in trait aggression. This heterogeneity helps explain why the same inflammatory message doesn't move everyone equally—but it does move the people most likely to act on violent impulses.

In contrast to the war/fight framing, emphasizing the values of democracy and pluralism can reduce support for violence. Last October, a huge study of over 32,000 participants identified key phrases and other interventions that successfully lowered anti-democratic attitudes and support for partisan violence. These included both in-party and bipartisan pro-democracy messages that emphasized shared values and democratic norms, such as:

Correcting misperceptions of how common anti-democratic attitudes, support for violence, and partisan dehumanization are among rival partisans

Vividly depicting the consequences of democratic collapse in other countries, including societal instability, violence, and economic turmoil (which, notably, increased support for partisan violence among conservative Republicans)

Featuring trusted and respected political leaders endorsing democratic and nonviolent engagement

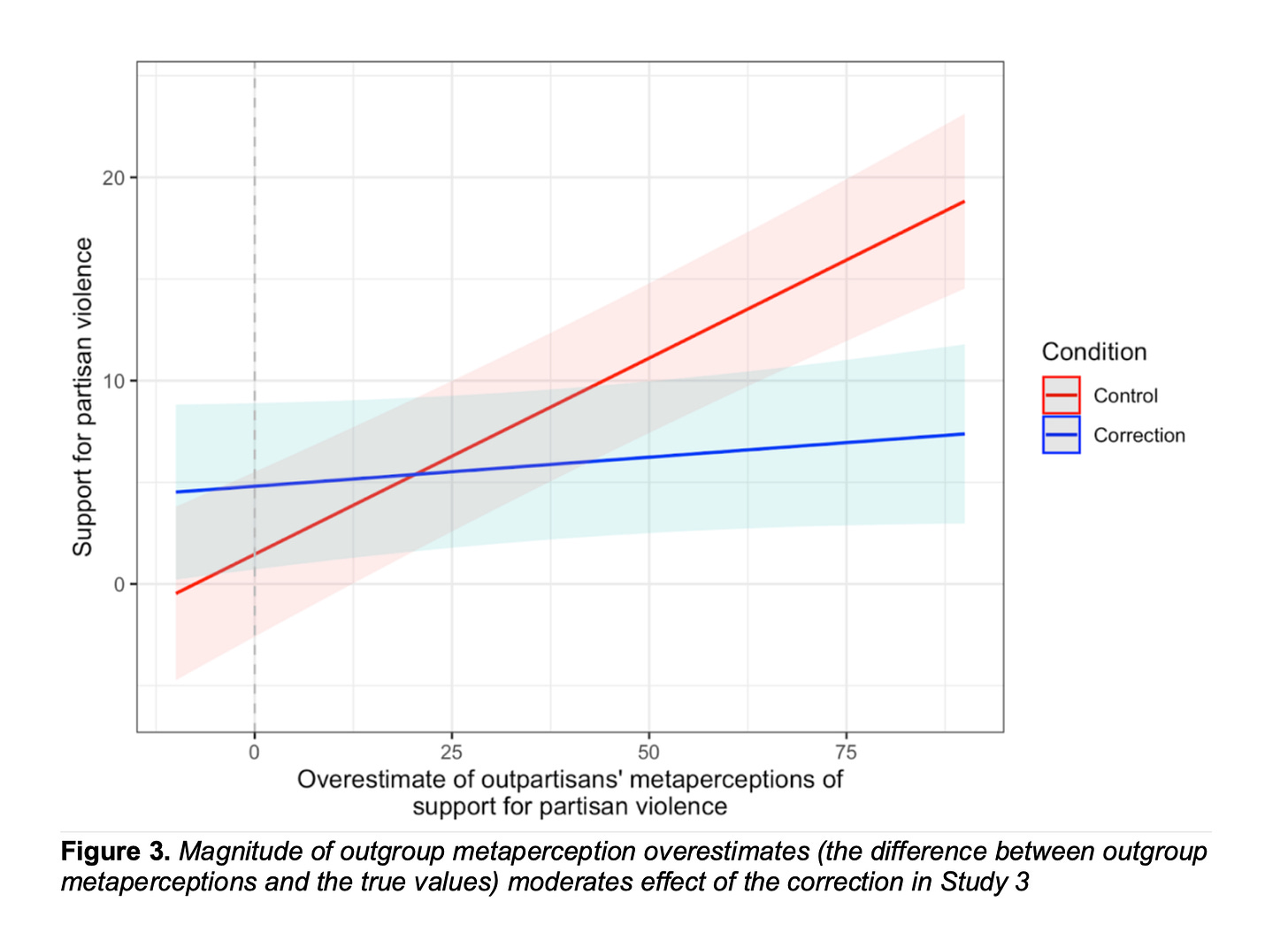

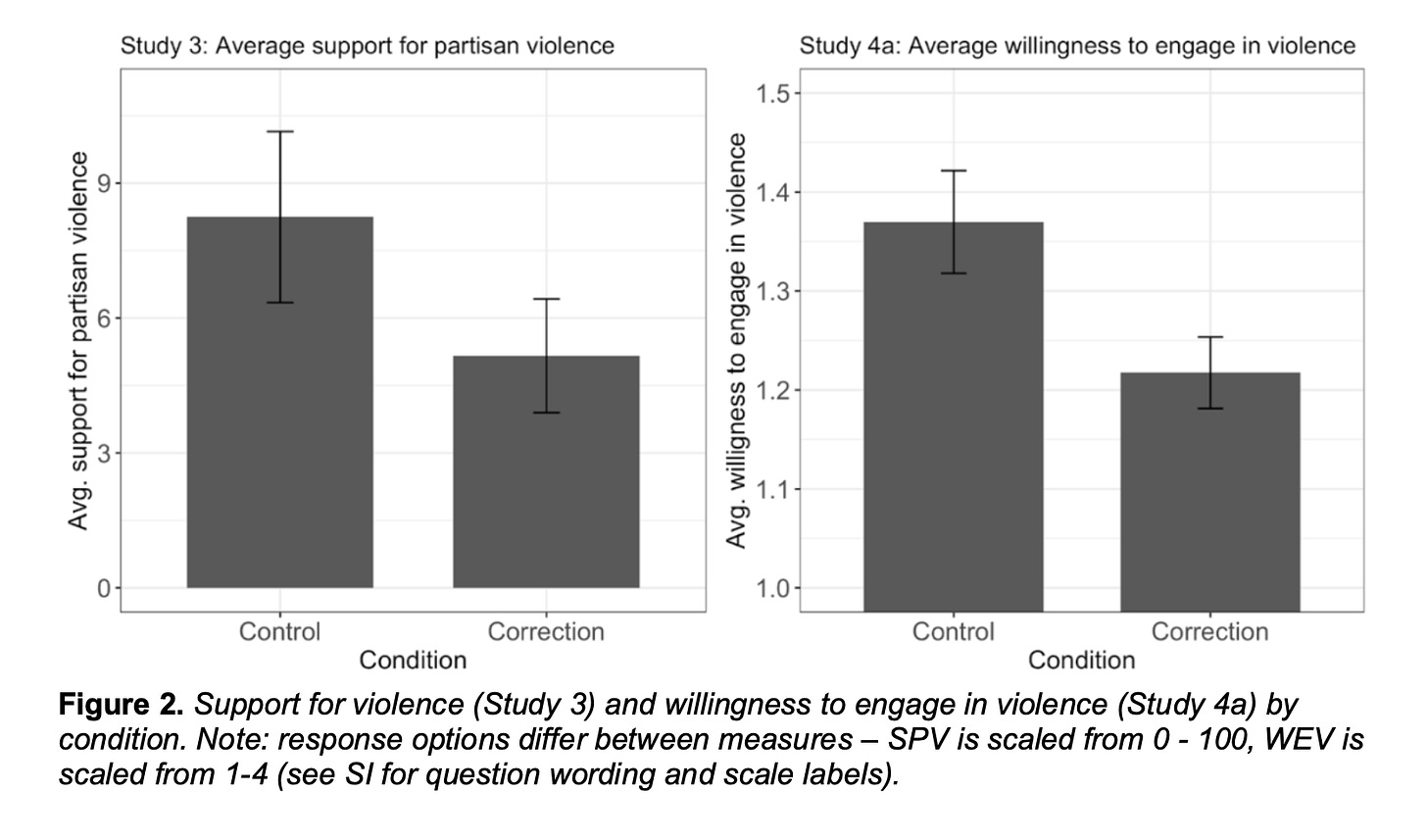

This finding on correcting inaccurate perceptions of support for violence is supported by another paper I’ve cited before, which concludes:

we found that both Democrats’ and Republicans’ misperceptions of their rival partisans’ support for violence and willingness to engage in violence were very inaccurate, with estimates ranging from 239% to 489% higher than actual levels. Further, we found that a brief, informational correction of these misperceptions reduced support for violence by 37% (Study 3) and willingness to engage in violence by 44% (Study 4). In the latter study, a follow-up survey revealed the correction continued to significantly reduce support for violence approximately one month later.

Here are two illustrative graphs from that paper:

Social media plays a role in fueling misperceptions and fomenting hate

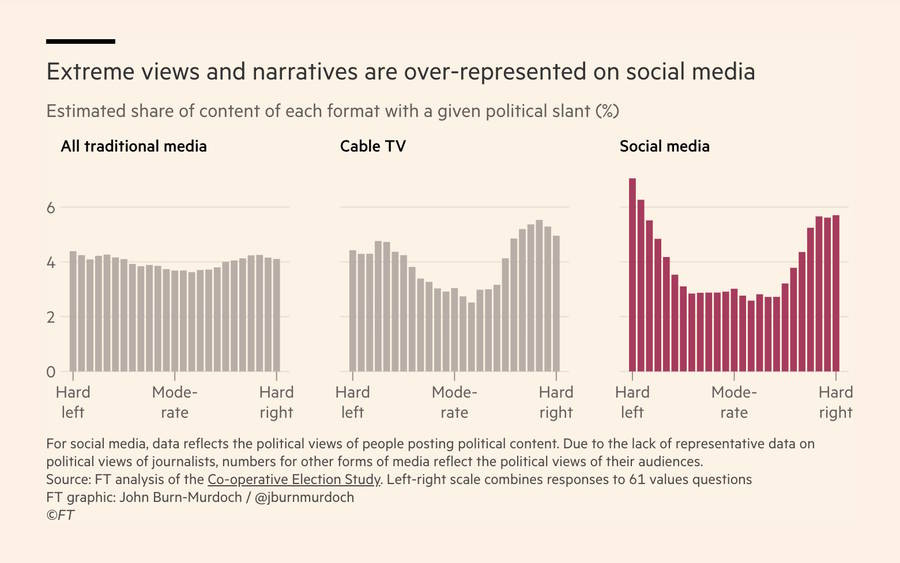

Another thing, somewhat secondary to this piece, this paper suggests is the indirect effect of social media on support for partisan political violence. Social media exposes users to the most fringe beliefs of the left and the right at a much higher rate than their incidence in the population as a whole, exacerbating misperceptions of the other party as a violent, fringe group made up entirely of Mao-loving Marxists or Orban-worshipping Fascists:

Taken together, the strongest claim we can make on the causality of political violence is that elite rhetoric can mobilize the small but consequential fringe most receptive to justifications of political violence. Elite appeals to shared democratic norms can pull in the other direction.

What calm, positive leadership looks like

So, what should leaders do after violence?

The 2025 paper from Kim on the link between elite rhetoric and mass support for violence suggests that in the aftermath of such events, leaders should engage in unambiguous, no‑exceptions condemnation of political violence of all kinds. Politicians and influencers should condemn violence and threats without caveat or collective blame. And as Kim’s work shows, this is exactly where cues from one’s own party are most powerful.

The Bright Line Watch research also suggests that figures should dial down the delegitimization of their political opponents in general. Rhetoric that paints elections or opponents as categorically illegitimate corrodes norms that ordinarily inhibit violence. Leaders can do this by repeating that we are “All Americans” and that “Any act of violence is un-American.”

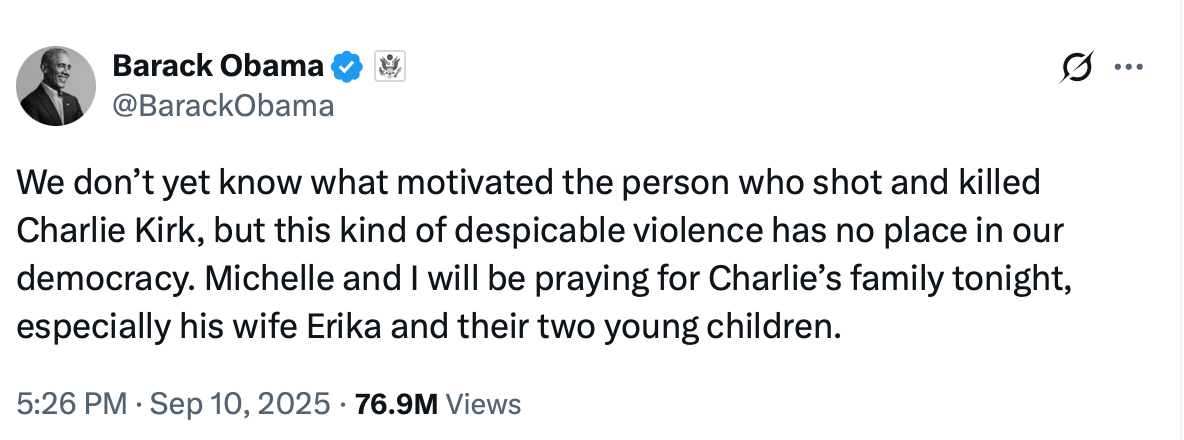

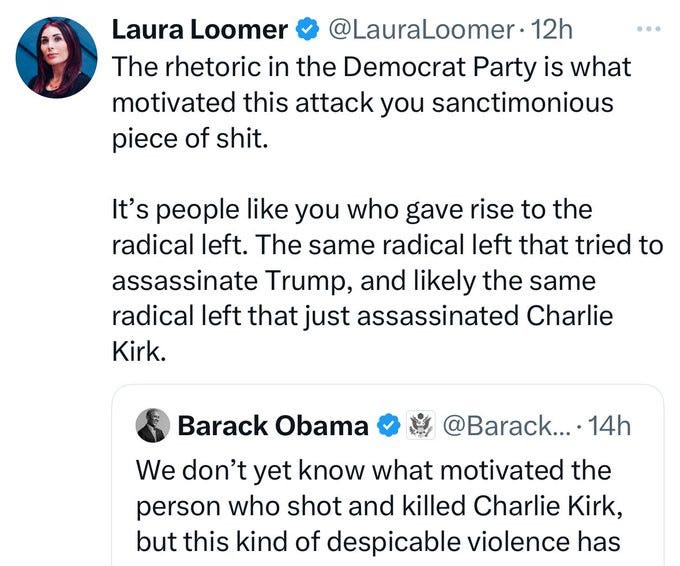

One example of a post that meets these criteria is Barack Obama’s statement after Kirk — someone he presumably vehemently disagreed with — was killed:

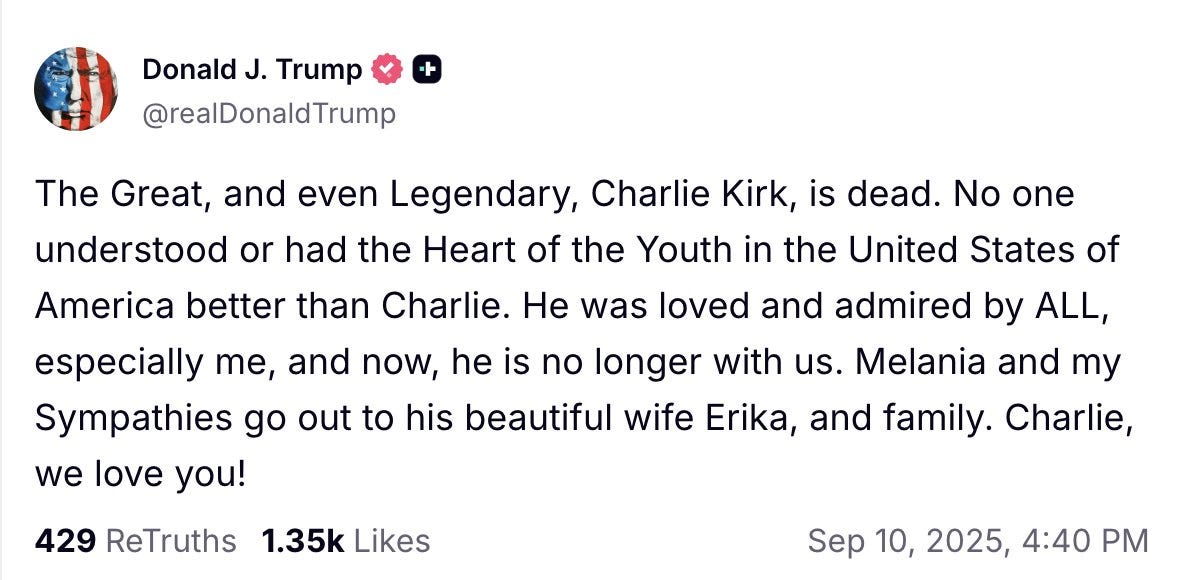

And even Donald Trump’s original statement on Kirk passes the test somewhat, celebrating Kirk’s life and giving his sympathies to his wife and small children:

“Sympathies” go out to Kirk’s wife, Erika — “We love you.”

What calm leadership doesn’t look like

If you’re not going to empathize with the victim or condemn all forms of violence, the advice from political scientists and psychologists is that a leader should, at the very least, empathetically celebrate the life of the deceased — and avoid stoking division or motivating a violent, us-versus-them framing.

And here’s where the data leads us to an unavoidably partisan conclusion. Unfortunately, it has become increasingly common for right-leaning politicians and influencers to use rare acts of violence to spread conspiracy theories about their political opponents. Immediately after the murder of the Speaker of the Minnesota House this year, right-wing politicians blamed the attack on “Marxists” and “radical leftists.” This included Utah Republican Senator Mike Lee.

When an assailant bashed Paul Pelosi over the head with a hammer in 2022, Republicans, including Ted Cruz, Elon Musk, Marjorie Taylor Greene, and Donald Trump Jr., all spread conspiracy theories about the attacker — including that he was a “radical leftist” and “hippie from Berkeley,” or that he may have been involved in a bigger false-flag operation to villainize Republicans. Trump Jr. made fun of him with a dumb joke about dressing up as Pelosi for a Halloween costume.

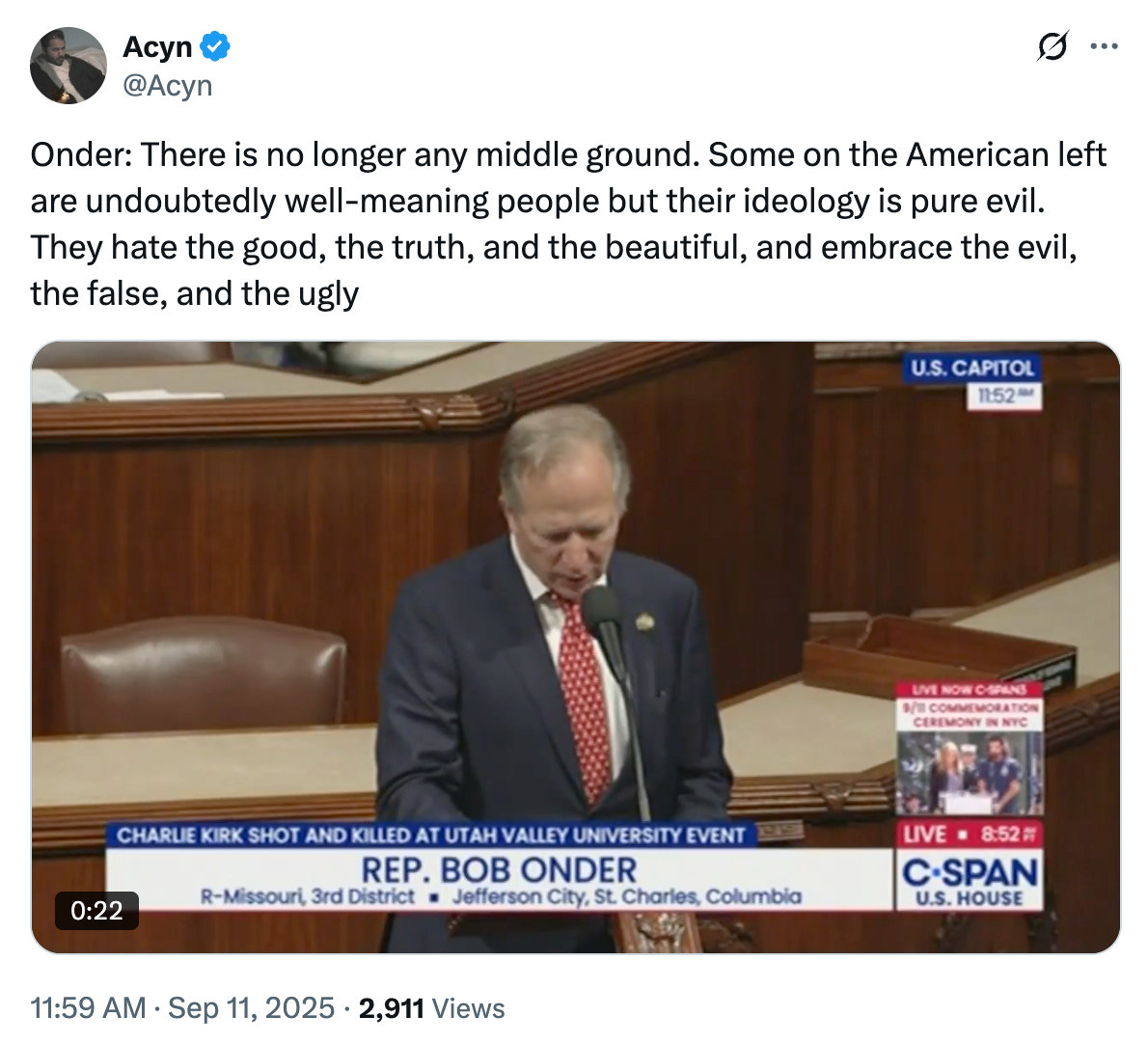

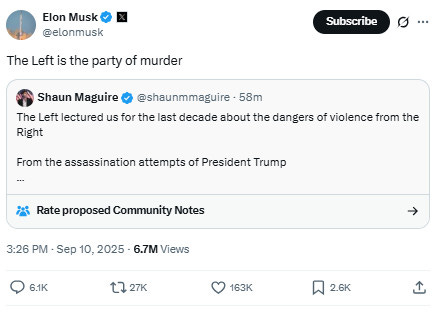

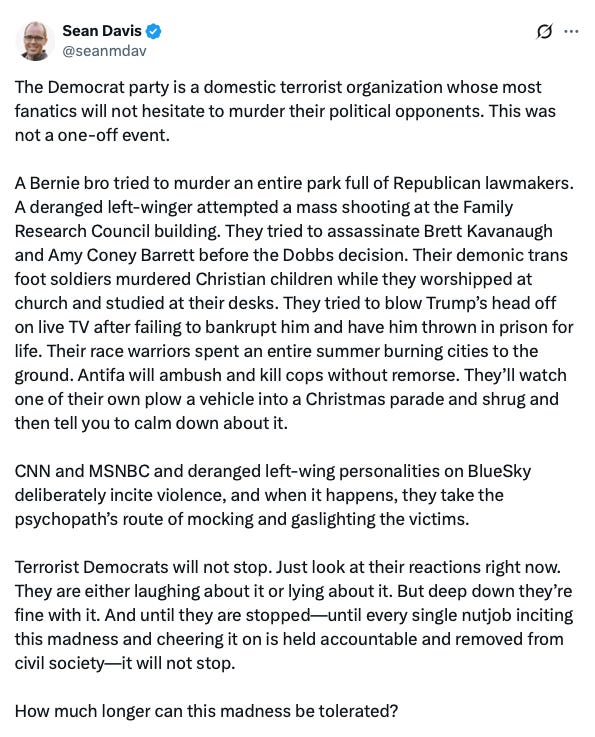

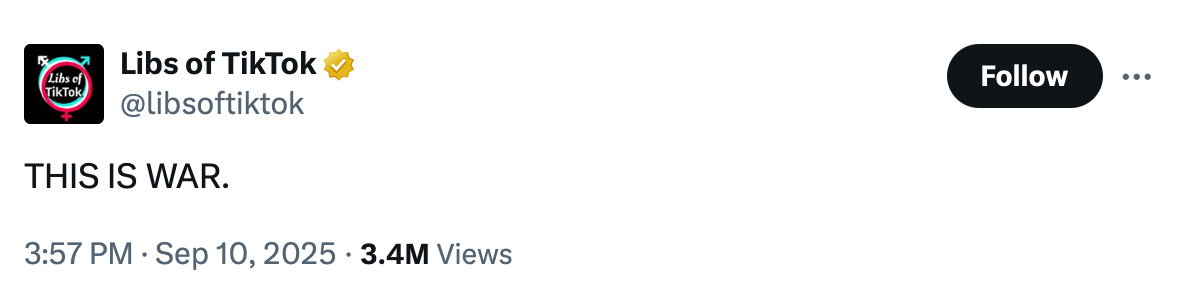

And unfortunately, the reactions to Kirk’s murder from his co-partisans are predictably bad and partisan. Here is a selection of some tweets from right-leaning politicians and commentators:

Rep. Bob Onder: The left “is pure evil”

Elon Musk: “The Left is the party of murder” — and also “If [the left] won’t leave us in peace, then our choice is fight or die”

Rep. Nancy Mace, who is running to become Governor of South Carolina: “Democrats own” what happened to Kirk.

Sean Davis, publisher of the right-wing website “The Federalist”: Democrats are terrorists and must be stopped: “until every single nutjob inciting this madness and cheering it on is held accountable and removed from civil society, it will not stop.”

2022 Republican candidate for Senator from Arizona Blake Masters: The FBI should take this opportunity to destroy the funding network for the Democratic Party:

The conservative “Libs of TikTok” account: “THIS IS WAR”

Unofficial adviser to the president Laura Loomer: “The rhetoric in the Democrat Party is what motivated this attack”

This prominent right-wing poster calls for Kirk’s assassination to become the “American Reichstag fire,” kicking off a (presumably violent) crackdown against their political opposition and the arrest of every single Democratic politician:

And finally, Wisconsin Republican Rep. Derrick Van Orden: The media “is responsible for that assassination yesterday.”

Trump’s remarks increase the risk of future violence

Also unfortunately, it appears that President Trump is not taking the higher road, instead veering onto the path towards demagoguery and affective polarization. In a speech Wednesday night, after Kirk was pronounced dead, the president echoed the calls from these lawmakers and influencers, fanning the flames of revenge and retribution:

It’s long past time for all Americans and the media to confront the fact that violence and murder are the tragic consequence of demonizing those with whom you disagree day after day, year after year, in the most hateful and despicable way possible.

For years, those on the radical left have compared wonderful Americans like Charlie to Nazis and the world’s worst mass murderers and criminals. This kind of rhetoric is directly responsible for the terrorism that we’re seeing in our country today, and it must stop right now.

My Administration will find each and every one of those who contributed to this atrocity and to other political violence, including the organizations that fund it and support it, as well as those who go after our judges, law enforcement officials, and everyone else who brings order to our country. From the attack on my life in Butler, Pennsylvania last year, which killed a husband and father, to the attacks on ICE agents, to the vicious murder of a healthcare executive in the streets of New York, to the shooting of House Majority Leader Steve Scalise and three others, radical left political violence has hurt too many innocent people and taken too many lives.

In an interview on Thursday, Trump said that he was going to “beat the hell” out of “radical left lunatics.”

This is all too familiar now. It has become increasingly common for right-leaning commentators to blame Democrats and Democrats alone for political violence. In a broader project to delegitimize the political opposition, the tragic murder of Charlie Kirk is an opportunity to crack down on liberals and the perfect encapsulation of authoritarian politics.

And of course, these events are not without precedent. Trump’s apparent strategy, as the “dissident-right” member Matt Forney above says, is eerily reminiscent of the Nazi response to the 1933 Reichstag Fire. Without evidence, Hitler blamed communists for the fire and used it to claim emergency powers from President Paul von Hindenburg, leading soon to the suspension of freedom of association and the press. Hitler dominated the next election and consolidated dictatorial power, then set Germany on a war path of retribution against its own citizens and the world.

I understand that Kirk was a particularly charismatic figure and close to many people in Trump’s orbit. Anger at his murder is understandable. But with leadership comes a responsibility to peace that cannot justifiably be shaken off with anger.

If your goal is to avoid future assassinations of political figures, you probably don’t give the speech Trump gave on Wednesday. And you do not call for civil or say Democrats are the “Party of Murder.”

The aftermath of Charlie Kirk’s murder is an opportunity for change

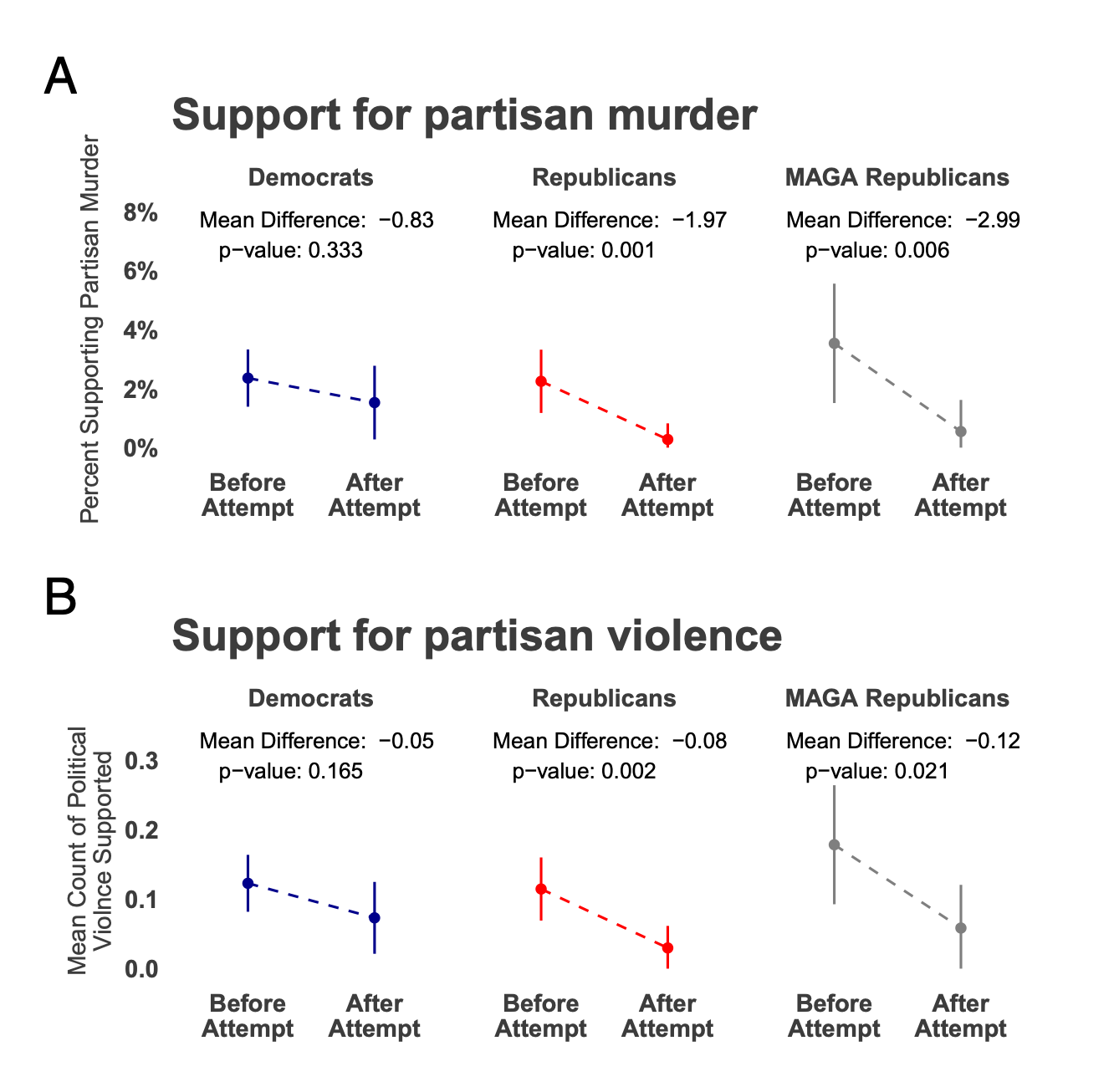

Here is another puzzle. In 2024, some researchers were conducting a national survey on political violence that just so happened to overlap with the attempted assassination of Donald Trump in July. This allowed them to study the effects of that event on overall support for political violence before and after the event.

It would have been reasonable to expect that the attempt on Trump’s life would have angered Republicans and increased their support for violence against Democrats. Remember, Trump rose from the ground after being shot in the ear, chanting “FIGHT! FIGHT! FIGHT!” and pumping his fist in the air triumphantly.

But the scholars found that in‑group support for partisan violence actually declined among Republicans after the shooting, and feelings of group solidarity (with fellow Republicans) increased immediately afterward. They write:

Using panel and cross-sectional interrupted time series analysis, we find no evidence that the event increased tensions or support for retaliatory violence in the immediate aftermath. On the contrary, Republicans, including MAGA Republicans, became significantly less supportive of partisan violence against Democrats. Republicans also did not become more hostile toward Democrats; instead, their attachment to their own party significantly increased.

Democrats experienced no change in attitudes. While nearly a third of Americans have no positive feelings toward the other party, and a supermajority have negative feelings, this animosity was not exacerbated by an extreme but salient instance of partisan violence.

The authors present this headline figure:

This study highlights that tragedy does not mechanically generate more appetite for violence. How leaders respond to rare, extreme acts of violence matters.

Now is the time for our leaders to act in accordance with the values of peace and pluralism that characterize a functioning democratic society.

Now is the time for positive leadership

I was not personally a fan of Charlie Kirk. I had my fair share of policy disagreements with him, and I believe he played a bigger role than most in the increase in affective polarization in America over the last ten years, the Republican Party’s increasing demonization of immigrants, and the rise of the alt-right.

But Kirk did not deserve to die for his beliefs. His children do not deserve to grow up without their father. In a democracy, even people you hate have the right to their own opinions, to speak, to run for office — and ultimately, to wield power. The social contract we have signed with each other rests on a basic commitment to the life and legitimacy of our opponents. Once that’s gone, the rest goes quickly.

To live in a functioning republic means turning down the temperature, even when we’re angry. For a better politics, brave leadership and calm heads must prevail.

This thoughtful analysis is why I subscribe!

Thank you for the clear and reasoned analysis. One point about the assassination attempt on Trump in Butler, PA is that the assailant did not appear to have a political motivation. He was registered Republican. He also had information about Biden on his phone. He seems to have been a mentally ill young man who saw this act as a way to be "famous." The attempted assassin in Florida was apparently a disillusioned MAGA supporter, who also appears to be mentally unstable.

I have been surprised that no commentators have mentioned the New Orleans attack earlier this year, which featured yet another rightwing shooter. Attacks have become so common from these fringe people that people forget previous ones as new ones emerge.