Meet America’s new swing voter: The anti-system voter. (Or: Why Democrats should think through nominating AOC in 2028)

A new paper finds anti-system sentiment — not left-right ideology — decided the 2016 and 2024 elections

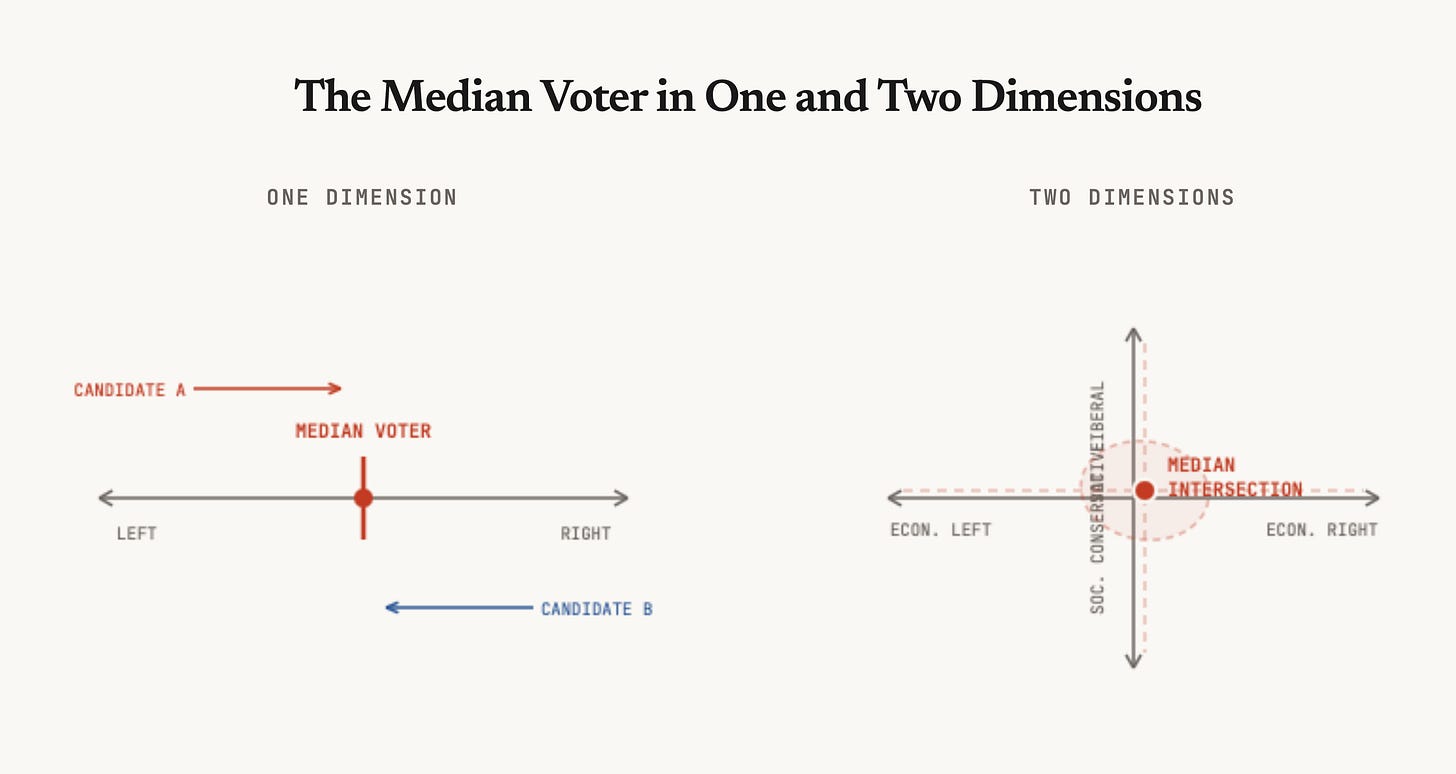

We are used to thinking of politics in terms of the left and the right. In the most famous (and fatally oversimplified) theory of voter behavior, the Median Voter Theorem, an individual votes for the candidate that most shares their values, beliefs, and issue positions — formally, the one that is “closest” to them on some set of important ideological and political variables. To win under the MVT model, a candidate has to earn the vote of the median American.

Many analysts expand the MVT to include multiple axes, or “dimensions,” of ideology. Instead of a flat line running from “left” to “right,” for example, you could say someone has different beliefs on “economic” and “social” issues. Winning then becomes a game of correct positioning on multiple policy domains — maybe the median voter is an economic liberal and social conservative.

But the MVT fails us in a few important respects. First, it assumes that the average person has both coherent beliefs and high political knowledge, which they need to determine how far away each candidate is from themselves. But thanks to survey data, we know that this isn’t true — most Americans in the “middle” are, in fact, non-ideological. I’ve written about this a lot over the last year, so I won’t rehash it here, but the upshot is that forcing every voter onto the 2-dimensional ideological grid doesn’t reflect how most people actually think about politics. This creates a false incentive to seek the “median” person on the grid, without acknowledging that the positions on the grid could be wrong.

The second big failure of the MVT is that it does not give us a way to think about the influence of attitudes that do not fall neatly on the left-right ideological spectrum. For example, where do you put a voter who says they want cheaper health care and also thinks the government “can never be trusted to do what is right”? And do we interpret that question differently in 2021 and 2026, when different parties are in charge of our government?

In 2016 and 2024, Donald Trump won so-called “anti-system” voters — including a lot who held progressive beliefs. So say political scientists Christopher Williams and Leon Kockaya in a new working paper comparing the role of anti-system beliefs to policy preferences in explaining Trump’s two victories, and his 2020 loss. Using survey data, Williams and Kockaya identify a key bloc of swing voters who distrust both parties, believe elites are corrupt, and think the political system is rigged against people like them.

In both of the years he won, anti-system attitudes were a powerful driver of support for Trump. Figuring out where these voters go in 2026 and 2028 will be key to understanding the outcomes of those elections. And to do that, you need to think beyond the Median Voter Theorem.

In this week’s Deep Dive, I explain why Trump’s superpower in 2024 could be Republicans’ downfall in 2026 and 2028.

This week’s Deep Dive is paywalled for paying subscribers. I don’t like paywalls, but the weekly premium post is a big part of what makes the subscription worth it for paying members. If you’d like to read it but a paid subscription isn’t in the cards right now, shoot me an email, and we’ll figure something out.