Midterms are a backlash, not a referendum

The best predictor of historical midterm election outcomes is which party is in power, not its performance

There are many risks to the American economy right now. President Donald Trump’s tariff war is putting upward pressure on goods prices. An AI-induced stock bubble could burst at any moment. Lower-income Americans are getting squeezed by higher prices and spending less overall, while spending more on credit. Federal debt is a potential problem, too. Unemployment is up. Net migration is down, which hurts growth, and the new situation with Venezuela threatens energy markets. A recession is not out of the question (but beware lazy predictions around 40%).

On the other hand, the stock market keeps hitting all-time highs. Maybe the AI bubble won’t pop, inflation will recede, and GDP growth will hit 5% this year. That’s not out of the question, either.

This uncertainty has people asking questions about the midterms. Would a crash hurt Republicans? If the vibecession ends, will the party hold its majority in the U.S. House? What about the Senate?

Let’s answer these questions, and more, in this week’s Deep Dive. The answer is not as straightforward as it seems.

I. Would economic growth impact the midterms?

This article stemmed from a great reader question I got the other week. Henry wrote:

Long time fan, hope you’re well! I’m sure you’re very busy with forward looking columns and books, but I saw something that instinctively seems wrong but could be a good retrospective column for the pre-primary doldrums.

Background: I worked for [redacted] for most of the 2018 Midterms. I recall that the main reason the Democrats had the wave election in the House was a combination of thermostatic opinion shifts and maybe secondarily the HC debate and the TCJA debate, both of which showed that Trump wasn’t for the little guy, but for the rich.

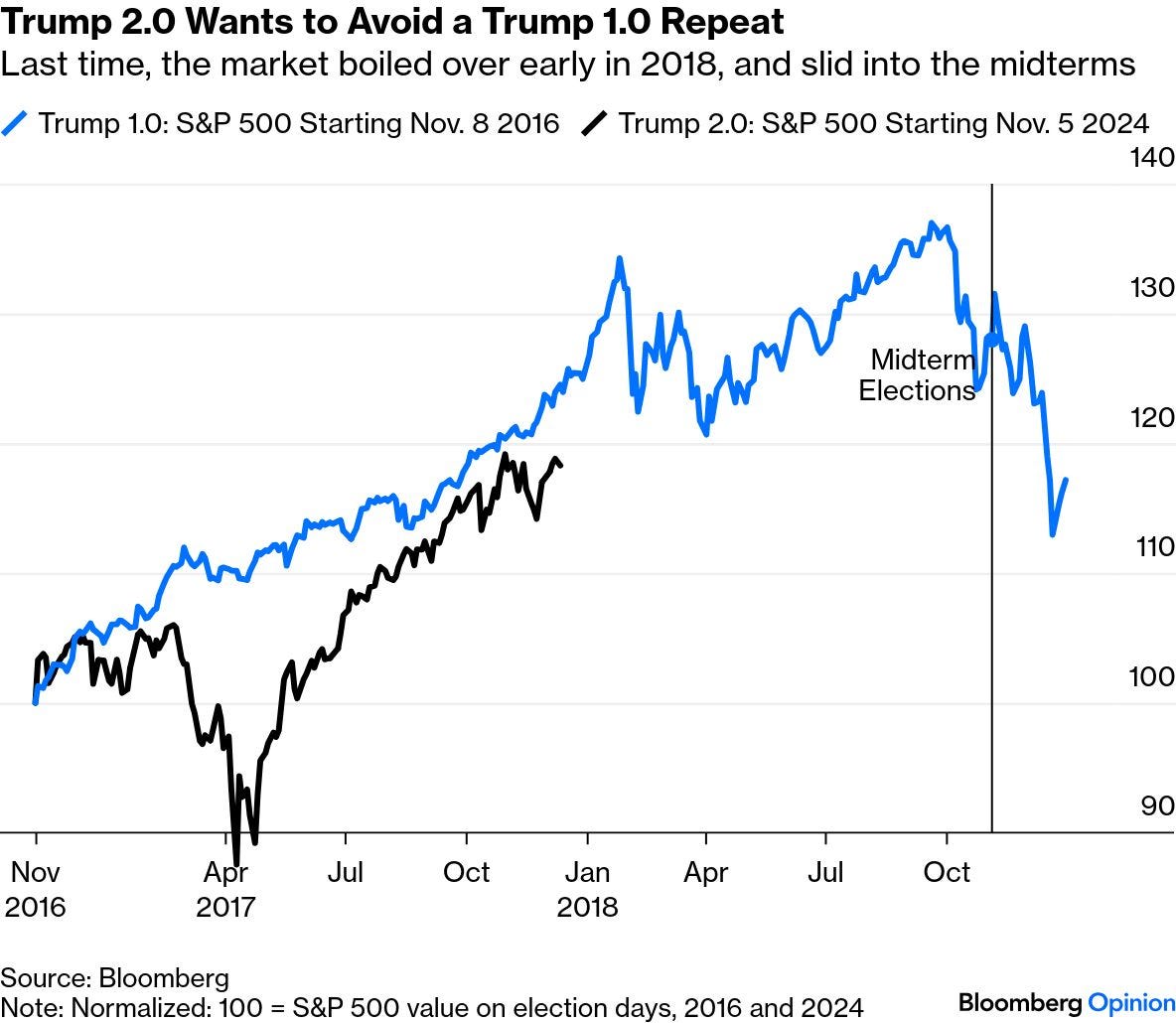

John Authers of Bloomberg (and maybe this is where my anger comes from; even thought he business press has even more reason to get things right over partisan nonsense; they do tend to have an immaturity about politics that is astonishing) wrote this a day or two ago:

“It will be hard but not impossible for Republicans to hold their majority in the House of Representatives next year, and it now seems clear that the economy will be the main battleground.

That opens up some interesting scenarios for the markets. The Trump team will be keen to avoid a repeat of his first term, when a much smoother debut in office ended in a melt-up as tax cuts passed late in the first year. That led to two ugly corrections in 2018 that contributed to the “Blue Wave” midterm victory for Democrats, and eventually forced an infamous pivot toward easy money by the Fed:

In this light, the fact that the S&P 500 is still stalled slightly below its high from October is almost positive. “

To my mind; this chart doesn’t show a correction really, it shows a flat economy from february to Election day 2018. My sense from old political science papers is that if you embrace the “pocketbook” theory of voting; the window for the effect is strongest between July 1 of an election year and Election day. I don’t know if you have the data but I wonder if the real reason for the swing in the House in 2018 wasn’t just mean reversion partisanship, rather than some indirect economic effect.

Full Gell-Mann amnesia in effect here, but an example of the press using political science (I think) Badly. But maybe I’m not remembering the causal chain of events correctly!

II. What I sent Henry

I love getting emails from readers. Here’s what I wrote back to Henry:

There’s something else wrong here, which is that growth in the S&P 500 — and economic conditions more broadly — do not typically predict midterm election outcomes. There’s no correlation between GDP change and seats won/lost, for example. Been meaning to write about that for a while and now maybe I will!

Of course, that doesn’t mean the economy doesn’t matter — but to the extent it does, it’s probably more closely proxied by things like the index of consumer sentiment etc and presidential approval than annual change in $SPY.

I’ve been meaning to write about this. Something to do more on soon.

This piece is me doing the “more” that I promised “soon.”

(The data for this analysis is linked at the bottom of the piece.)