You should quit social media for good

Platforms optimized for engagement warp our politics, erode attention, and harm our wellbeing. Here’s how I minimize time on the (anti‑)social web.

This essay will be most useful to knowledge workers and young people, but I imagine it will be of interest to anyone generally curious about the impact of social media on politics and our lives today. The piece tells my personal story of how I leveraged social media to build a career as a writer and political analyst, and then why — and how — I left most of these sites in 2025.

My thesis is that sometime around 2017, social media companies began a transformation into what I now call the anti‑social web. This transformation primarily resulted from the emergence of big data and algorithmic recommendation systems, which can individually target posts to users that maximize engagement and time spent on the platform.

If you look at the scientific literature today, the empirical harms of these platforms now clearly exceed the benefits the vast majority of users get from them. Unless you have to use these platforms for work, it’s time to quit them — or minimize the time you spend on them — for good.

Anti-social media

Social media is having a bad year. Usage is declining. Books, including Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation, advocate outright bans on most social sites for teenagers. Many states have listened and now prevent students from using cell phones in schools. The assassination of Charlie Kirk in September showed how radicalization can happen in plain sight — something Congress is now investigating. Meanwhile, bot farms and AI-generated content — not to mention faux posts from advertisers — clog our feeds and crowd out truly social interactions.

Most adults today know that social media is bad for them. Still, my feelings toward platforms are complicated. On the one hand, as we’ll see, their harms are demonstrable and affect even the most careful users. There are plenty of very good reasons to stop actively using social media platforms altogether. Yet I acknowledge the utility of an interconnected web, especially for writers (like me) who need to share their work with new people. I personally owe my career in large part, if not entirely, to the discovery effects of social media: In college circa 2015, my future editor at The Economist discovered I existed because I was blogging about election forecasts and polling and publishing links to these articles on Twitter.

But this was Old Twitter. Anyone who has been on these platforms for any measurable amount of time has realized that the experience of the social web has changed since then. Social media services in 2025 feel completely different than they did 5 or 10 years ago. Posts now seem more fake, more negative, and more algorithmic — and, notably, less social. When was the last time you saw three posts in a row from your friends on Instagram or TikTok? Social media websites today use algorithms to select posts to show you from a corpus of hundreds of millions of candidate posts — the vast majority from people you would not socialize with in real life.

In 2015, you could be forgiven for wanting to post silly little tweets to get attention from your friends — or even to publicize articles you were working on to get noticed by future employers. But here in 2025, the social web does not work like this anymore. It is, in fact, an anti-social web. Due to pressures from shareholders and advances in artificial intelligence, platforms are now by design consumption media, or maybe attention media — but certainly not social media.

Today, the AI-generated slop flooding social media — in some cases, with companies branding the slop itself as social media — is also a concern. How long will social media even remain majority human-generated? I don’t know about you, but I have no interest in seeing AI-generated Twitter posts of Kid Rock, Hulk Hogan (as an angel), and Tucker Carlson praying over Gavin Newsom (yes, this is a real Twitter post sent by the Governor of California):

In response to the vanishing utility of algorithmic social media platforms and the growing body of empirical evidence on the harms they pose to users, I have made several changes to the way I use social media this year. These changes have improved my focus, increased the quality and quantity of my work, and, perhaps paradoxically, allowed me to spend less time working — giving me more time to spend with family and on hobbies (I’m an avid gardener, exercise daily, and have recently gotten into modding old laptops with newer computer hardware and software — don’t @ me).

These changes came at a critical time in my life. Circa Summer 2025, with no regular employment, I was under extreme pressure to produce high-quality work that people would pay me for. This included writing, a skill that requires a lot of focus, and also coding up complex analyses of survey data for consulting clients. I knew if I under-delivered for people relying on me, those income streams would dry up, too. Yet I couldn’t find the time or focus to feel good about what I was producing.

But the spare time was there, I was just spending all of it on my phone — an average of about four hours per day, mostly on Twitter and YouTube. With a few simple (not necessarily easy) changes, I’ve been able to reduce my screen time to 45 minutes per day or less (except on Sunday, when I use my phone for fantasy football). For the most part, the tips I share below are not my original ideas, but developed by people such as computer scientist and anti-social media evangelist Cal Newport.

I’m writing this post because I think there is an off chance it will be helpful for people who are in a similar position to the one I was in early this year. This post is for people who need that final push to reduce their use of social media, or even their phone more broadly.

At the level of the individual, I think this will help you feel more grounded, reduce your stress, produce better work, and unlock more free time. At the societal level, the hope is that if enough people stop using these platforms, we may be able to reduce social harms like polarization, political violence, and loneliness/suicide dramatically — especially for young people. (The only social media you need is the comments section of this newsletter.)

Social media is all algorithms now

To understand what went wrong on social media, you need to understand how these platforms decide what to show you when you log in. When Twitter was first created in 2009, all users saw was a timeline of posts sent by users they explicitly followed, sorted in reverse chronological order of when each post was sent. It was like reading a friend’s diary: If you saw a building on fire, the expectation was that you were supposed to post that you saw a building on fire. Now aggregate that to the nth connection.

Yet over the past decade, every major social media service has undergone what Newport calls “the algorithmic turn.” Let’s take Twitter, my former site of choice, as an example of this turn.

While it’s true that the fundamental purpose of Twitter changed in 2022 — when Elon Musk bought it and turned a microblogging and mass communication service into a megaphone for the political right — the platform actually began its decline earlier, in 2016. That’s when the website discontinued its reverse chronological feed of posts from people you followed and started serving up algorithmic recommendations to users. The business genius of these algorithmic systems is that they can predict which posts you, as an individual, are more likely to engage with (measured mainly by quote tweets and retweets of similar posts), in turn maximizing the time you spend on the platform — and thus the number of ads you consume.

Since 2016, the transformation from social media to the anti-social web has accelerated at an exponential rate. Thanks in large part to the development of the artificial intelligence algorithms (notably, embedding tables and transformers) that underpin large language models such as ChatGPT, social media companies have become much better at recommending content you will engage with. This is not just happening on Twitter, but on every social media platform, including TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, and even Substack. What you see on these platforms, particularly TikTok and Instagram, is now much more biased to what an AI model thinks will keep you scrolling on the app — including posts from random users around the world — rather than what your friends post.

As a result of the algorithmic turn, platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter/X are not “social” media anymore. We do not use these services primarily to connect with our friends. Instead, they are simply avenues for consuming posts that an algorithm has decided will have the maximum possible impact on the amount of time you spend on a platform. They are vehicles for converting your attention into impressions for advertisers — and, in the case of Twitter (which lets users pay to have their posts ranked higher by the algorithm), other paying users.

Social media use poses numerous harms to users

But this doesn’t really sound so bad, right? If someone interested in the gym wants to spend their time on Instagram getting fed hours and hours of short-form video of people lifting weights in a gym, is that actually posing a harm to users?

The data suggest it is. Algorithmic recommenders pose many harms to users, but in this piece, I’m going to focus on the following four: affective polarization and echo chambers; motivation to engage in acts of political violence; threats to mental health, especially isolation and suicide; and declining capacity for critical thinking and, of course, meaningful productivity.

1. Social media increases affective polarization

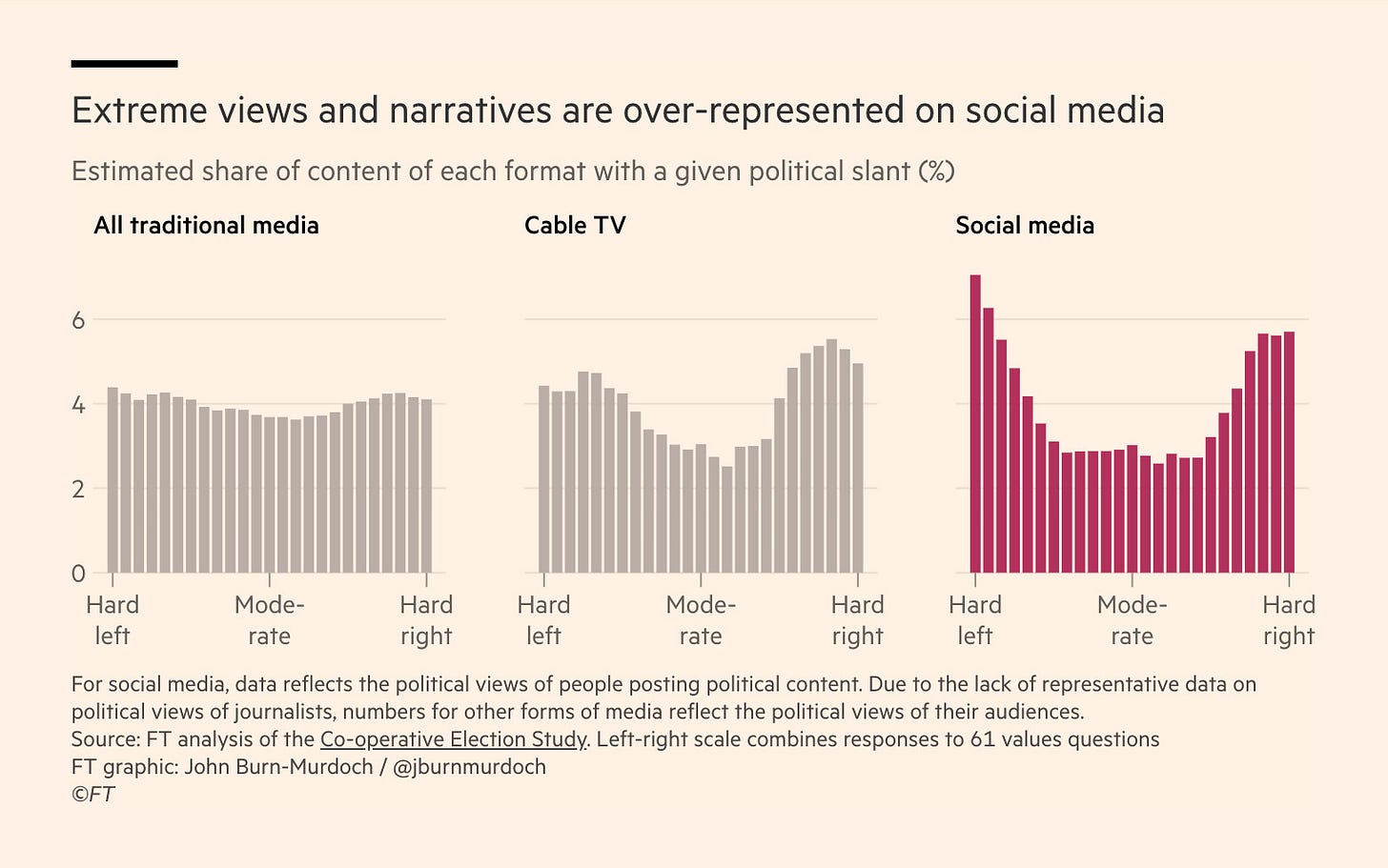

One problem of social media is that the people who use online communication platforms tend to be much more ideological than the population as a whole. The following chart from the Financial Times portrays this dynamic elegantly:

Compared to the people who digest other forms of media, social media is much more ideologically polarized to start with. This exposes users to a much higher proportion of far-left and far-right content than exists in the general population. Most Americans are not far-left or far-right, but you wouldn’t guess that based on the types of people who post on Twitter or TikTok.

Then, there are the algorithms. As discussed above, algorithms don’t just show what you “like” — they predict what will make you react. The result is affective polarization — a deepening hatred of out-groups, even when people’s actual policy differences remain modest.

Four years ago, I wrote a book review for The Economist of sociologist Chris Bail’s Breaking The Social Media Prism: How to Make Our Platforms Less Polarizing. In this book, Bail introduces the concept of seeing social media apps as a prism, distorting reality as a prism would distort light. The social media prism takes in one image of the world as captured through massive amounts of text or video that are entered into the platform by other users, and then spits out a new vision of reality tailored exclusively for you.

As Bail shows, the output of the social media prism is angrier, more negative, and — importantly for this piece and this newsletter — more ideologically polarized than the content users are actually posting. The result of this is that social media algorithms dramatically amplify the views of ideologically extreme users.

This over-representation of our ideological extremes is inherent to platforms that use algorithms to maximize user engagement. That’s because emotional, moralized content drives engagement. The cycle here works as such. First, a user from the fringes will post something outrageous, maybe something like “Jews killed Charlie Kirk“ or “Kamala Harris is a Marxist.” Then, other users will quote tweet and engage with that post, some signaling their approval, but many others signaling their outrage. The algorithm picks up this engagement as a positive signal to recommend it to other users — remember, all the algorithm knows is that it’s supposed to recommend highly engaging content. As a result, everyone sees the most outrageous, ideological content generated on the platform.

Bail also finds that users tend to react more negatively to posts from the ideological pole that is opposite their own ideology. This again can get interpreted as a positive signal to recommender algorithms, causing a center-left (or center-right) person’s social media feed to get flooded with content from the far-right (or far-left).

Social media doesn’t necessarily change your ideology, but it does warp your perception of what others believe. This has the consequence of polarizing you against your perceived political opponents. The more time you spend on social media, the more likely you are to think “everyone on the other side is crazy,” because the most extreme, viral voices dominate your feeds.

This is bad, for starters, because it decreases incentives for collaboration across the political spectrum and raises incentives for our political leaders to engage in ideological conflict. But it can also have fatal consequences:

2. Motivation toward political violence

Research has shown that the types of misperceptions generated by social media inflate support for political violence. The mechanism here is simple: Once users are exposed to violent rhetoric — or even claims of violent rhetoric — coming from the other side, they become more likely to support such violence themselves.

This is worsened by recommendation algorithms that reward identity-based anger and moral outrage. Platforms condition users to see opponents not as neighbors, members of their social network, but as members of far off-tribes that are a threat to their own. From there, it is a slippery slope to justify violence against members of the opposition group.

The young man who killed Charlie Kirk in September, who appears to have spent much of his time in politically active Discord channels, justified his actions, saying he “had enough of [Charlie Kirk’s] hatred. Some hate can’t be negotiated out.” Days later, Elon Musk blamed the left and said, “violence is going to come to you, you will have no choice. You either fight back or you die, that’s the truth.”

Worse, because discovery has effectively been centralized into machine‑learning ranking systems, fringe ideas can “jump” from tiny subcultures to the main feed almost overnight. This is due to the amplifying effects of algorithmic recommendation systems. These systems can spread a single post to millions of users identified as members of the same or similar social networks as the poster — and then, in turn, to users identified as belonging to the same group as the re-poster — it takes only a fraction of the number of posts as you think to move the beliefs of an entire, ideologically aligned group.

To be clear, political violence is very rare (and inflated in most polls). Most of us will never pick up a weapon, or sanction direct violence on someone we know. But algorithmic social media platforms provide two “solutions” for people who might otherwise not commit violence: discovery and coordination. Recommendation algorithms can help an isolated, disaffected person find a group that echoes his grievance and legitimizes violent behavior. Then, other online communities — such a niche Discord servers — can take over the radicalization from there.

3. Impacts on mental health

The paradox of algorithmic social media is that the more “connected” we become online, the lonelier we feel offline. That’s because the time we spend in our AI-driven hyper-optimized digital reality displaces the time we could otherwise spend with people in real life.

The result, particularly for adolescents and young adults, is higher reported anxiety and depression, and a persistent sense that everyone else is doing better than you. Smartphones have been linked to higher rates of depression and suicide among young people, particularly adolescent girls. It seems like people have finally come around to the view that spending all your time comparing yourself to the people you see on Instagram is not good for your mental health.

But less extreme outcomes, while not nominally as bad, still plague users. The average American adult spends between 4 and 5 hours on their phone per day. Assuming they aren’t sending emails this entire time, that’s a long time to be swiping, scrolling, and consuming on a small device 2 feet in front of your face. In general, the more you use your phone, the more isolated you will feel.

Of course, this is by design. Social media companies and app programmers have various tools to incentivize you to keep using their services and racking up ad impressions. Innovations such as infinite scroll for feeds, variable rewards in boosting your posts to other users, and other features turn phones into portable slot machines. We haven’t even touched on what this can do to your sleep.

If this isn’t enough to get you to put down the phone, just for a second, consider what you’re getting in return for your elevated risk of depression and suicide. Are you making connections you wouldn’t otherwise make? Are they rewarding to you? Are you ingesting information that is helpful to your job or a passion you couldn’t find elsewhere?

Then, it helps to imagine what these services will look like a few years from now. Are you setting yourself up for disappointment? AI also threatens to exacerbate the harms of chronic social media use. First, because AI-powered recommenders are exceptional at keeping you on your devices. And second, because “social” media companies such as Meta and Google are leaning into AI-generated content. First, they got America addicted to social media. Then, they took out the real social connectivity, while amping up the addiction. Soon, these platforms will be mostly AI-generated entirely — posing the question of what we’re “connecting” with anyway.

Understand politics with data, not spin.

Mainstream coverage of politics is lost in the noise of partisan spin and an understanding of elections found in Government 101, not reality. Here at Strength In Numbers, I explain our world using hard data and statistical analysis. SIN offers paying members exclusive analysis that goes beyond headlines to reveal how voters truly make their decisions — and covers what the media is missing.

Get premium independent, fact-based political journalism with a paid membership to Strength In Numbers today, and get other perks like a private Discord community and access to early releases of new data products.

4. A meaningful hit to productivity

Maybe this is enough to convince you not to give your kid an Instagram account, but you think you’re insulated from these harms. First, statistically, you’re not — no one is immune from the virtual slot machine that is the modern social media platform. But second, the research suggests that your smartphone also impacts your productivity, critical thinking skills, and memory. Are you willing to trade your career for your smartphone?

Consider how often you spend thinking about a problem at work today. Maybe your boss sends you an email or Slack message asking for a report on your company’s quarterly output by tomorrow morning. Do you have the discipline to start that task immediately, and to stay on it until you’re finished? Or do you maybe open a Microsoft Word document, start outlining the report, and then tab over to Twitter to see what’s up with the world? Maybe you get the itch to fish your phone out of your pocket, fling it into the correct orientation, and open TikTok. Maybe this happens without your conscious input at all — your subconscious has just decided you deserve a little dopamine hit, as a treat.

High-caliber knowledge work today depends on the ability to hold a complex problem in your head and push it forward without interruption. But basically everything about your phone is set up to degrade your ability to focus on anything other than your phone for any meaningful period of time.

Studies of knowledge workers (basically, anyone who works a desk job in an office) show that interruptions like the above trigger “chains of diversion” that distract you from the task at hand, and then send you on subsequent rabbit holes without you even noticing. This, in turn, creates substantial lags in your focus — with each subconscious Twitter break costing you about 15 minutes of productivity while your brain gets back on track. In the academic literature on this subject, scholars say distractions create an “attention‑residue” effect where even brief “context switches” degrade performance on the next task. The idea behind context switching is that the hard parts of writing, research, engineering, design — all of it — require boring (and steep) ramp‑up time before anything interesting happens. When you get distracted, you get pushed off the ramp and have to climb it again.

Further, the evidence suggests that even the mere presence of your smartphone in your physical vicinity distracts you and reduces long-term productivity. If your phone is on your desk, your brain is constantly thinking about what you might be missing, which friend may have texted you, what someone on social media may have said about a recent blog post you published that they didn’t like. When you eventually pick up your phone (come on, it’s right there, what’s the harm in a quick 5-minute Instagram reels break), you kick yourself back into the attention deficit problem above.

Conclusion of harms section

This is an awful lot about the dangers of social media and phone use. But that is partly the point: Here in late 2025, we have enough empirical evidence to know that these technologies are bad for us, and we should avoid them if we can. Other people have written much longer (and better formulated) summaries of the research on this subject, and I hope I haven’t botched it.

So, given these harms, what should you do next?

Social media hygiene: The good remaining platforms

First and foremost, if you can quit social media, I think you should. But if you absolutely have to use social media for your job (maybe you’re a journalist and your editor says you need to spread your work, or an artist and you crave art inspiration), I would advocate switching away from services that use algorithmic recommendations. For me, a politics writer, that has meant switching from Twitter/X to Bluesky.

I know it’s popular on Twitter to beat up on Bluesky for being a cesspool of leftism, and the platform does (gleefully) participate in the dunking culture that made Old Twitter annoying as well. But in general, I think this is a bad critique that overlooks the main benefit of the platform: the lack of an algorithmic recommendation system. (Actually, Bluesky does support algorithmic recommenders, but they do not come built-in to the platform — you have to code and supply them yourself.)

When you open Bluesky, you see a good old-fashioned reverse-chronological feed of posts from people that you have selected to see posts from. There is no Grok-powered AI “For You” feed, and you don’t see posts from random users who have paid to have their content sent into your feed (as if you wanted to see a post from StormedTheCapitol69420). For people who gather information for a living or want to stay plugged into certain conversations or writers’ work, Bluesky is basically Twitter in 2014. Again, there is an ideological bias and mobbing problem, but both of those problems are going to exist on any platform. With Bluesky, you avoid algorithmic recommenders, which is really what has made the modern web useless.

Additionally, Reddit and Substack are also good “social media” platforms, if what you care about is reading posts from people in the same community as you or people you have opted into receiving newsletters from.

But the common platforms, the platforms everyone is spending 4 or 5 hours a day on — TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube etc — need to go. Odds are you aren’t getting as much from these platforms as you’re putting in — and the distorting effects they’re having on our democracy are also not worth what we’re collectively getting out of them (NASDAQ go up, I guess?).

What to do if you need popular social media services for work

First, no, you don’t. Plenty of Pulitzer Prize-winning reporters and 10x coders have achieved the heights of their industry without social media. You can too.

But if you do have a need for these apps, then it’s worth thinking about what features the ideal social media website would provide you — and what you should avoid. For a first approximation, I think the ideal platform should:

Help you keep up with your friends and family

Connect you to real people who might consume your work in real life

Promote thoughtful engagement about a topic or work

Help you discover work from people you wouldn’t otherwise know about

And while this isn’t exhaustive, the drawbacks of modern platforms come with things like:

AI-powered algorithmic recommenders

The pressure to perform/incentives toward growing your “follower” count

Saturation of feeds with ads and marketing

You should minimize your use of platforms that have features that mostly fall in the negative zone above.

Regardless of the platform, I advise you to use a post-scheduling service such as Buffer or Publer to automate your posting. You can use these apps from your phone or, preferably, your computer. I personally use Buffer. Using a service like this means that all of your genius musings and recent Pulitzer-winning articles still go out to your followers, but you don’t have to open the app in the middle of your workday, risking the consequences of context switching and other distractions.

Then, you should delete all the social media apps from your phone. Yes, all of them. Nobody needs 24/7 access to Twitter or Instagram. You can use the web interfaces for these apps to send new posts and interact with your friends on DMs. Optimally, you will get to a place with your phone that you never feel the subconscious pull to open an app to perform some action that gives you a dopamine hit. This short-circuits the feedback loop that causes you to keep opening them, even when you know about the harms or don’t get utility from them anymore.

Phone hygiene: Treat it like a landline

I have written a lot about social media and not much about smartphones. Phones have their own problems too — e.g., the risks in the attention-hijacking-by-proximity paper above. So here are a few tips for decreasing your screen time in general. Each of these has done wonders for my relationship with my phone.

First, treat your phone like a landline (AKA the “phone foyer” method). My phone stays plugged into the charger, in the same place, all day, every day, unless (a) I need it or (b) I leave the house. If I need to send a text, I walk to my kitchen, grab my phone, and send the text. The phone returns to the charger once I’m done. If I need to answer (or send) a FaceTime call from my parents, I go to my phone, take the call from wherever I want in my house, and then return it to the charger.

When I’m home, I keep my phone plugged in on my kitchen counter, pictured here:

The key here is that you have a spot that you mentally associate with using the phone, freeing up all other areas of your living space/office/etc to be “no phone” zones. I don’t use the phone on my couch or in my bedroom (or, god forbid, the bathroom).

Second, schedule time in the day to check your social accounts. If you use one of the services I mentioned above to schedule your social media posts, then you really don’t have any need to stay logged into these accounts. My advice: Have a set 30 minutes every day where you log into your accounts, check mentions and DMs, maybe quote a post or two, and then log off. My social media hours are between 11:30 and 12 every day — and only if I don’t have something more pressing on my to-do list.

Third, schedule your email time, too. Following the above, I also recommend batching your emails. I also don’t check my email (or Slack) until 11:30 every day (I clear my inbox before doing my social media workflow), and limit email time to that window. If I know something important is coming my way in the afternoon, I’ll check my email and Slack again in the afternoon before quitting work.

Finally, I recommend silencing all notifications from your phone except calls from your boss and loved ones. You don’t need an audible ding every time someone likes your Instagram post, or whenever The New York Times publishes a new article. Transforming your phone from a pocket computer into an old-school phone is key to rewiring your relationship with technology. Again, the key here is to mentally associate your phone with communication (preferably audio communication), and not with the social validation you might occasionally get from social media apps.

Conclusion: Get off your phone!

To summarize: The social web stopped being truly social some time ago. When you stop treating these apps like you would if you were having a conversation with a friend and start treating them like an extractor of your attention, the choice is obvious: it’s time to log off.

If you do log off, your work and life will get better. I find this is true from my personal experience, but also from the mass of social science on the subject. The recommender‑driven feeds that once helped me find readers now mostly help advertisers find me. You don’t owe your best hours — hell, your best years — to an engagement machine.

Yet, contrary to YouTube self-help videos and the advice from your luddite cousin, you don’t have to go off‑grid to opt out. If visibility is part of your job, use reverse‑chronological spaces (newsletters, forums, Bluesky) and a scheduling service so your work reaches readers without keeping you in the feed 24/7. Deleting the apps from your phone, keeping your phone on a “landline” spot at home, and batching your check‑ins (via your computer!) once a day (at most) can also help reduce screen time.

If this seems hard to you, run the fixes above as 30‑day experiments. Track your screen time, focused work hours, and your mood. If you’re not better off, you can always undo the changes. My personal experience from helping my friends is that most people won’t want to go back to a world where they have apps constantly competing for their attention.

The personal gains are reason enough to quit social media. More focus, better output, more free time, etc. But there’s also a major civic upside. Every hour we reclaim from our social media owner class weakens the incentives that we all face toward polarization, outrage, violence, loneliness, and distraction.

So start moving away from your phone today. See what you can build when your attention belongs to you again. What do you have to lose?

I forgot to put this in the article, but another thing I recommend is turning off iMessage on your computer. That's what your phone is for!

The nudge I needed. I'm following your lead. Thanks!