Trump is racing against time

The president's approval rating is closer to Nicolás Maduro's than Vladimir Putin’s

This post is largely a response to an article Paul Krugman published last week. Krugman asks, in “Is the Jimmy Kimmel Saga a Sign that the Tide is Turning?”, whether Trump is finally overstepping the bounds of public opinion so much that elites who had been previously following his lead are now wavering:

As [Trump’s] poll numbers fall, he is rushing to lock in permanent power by punishing his opponents and intimidating everyone else into submission. Craven congressional Republicans and a complicit Supreme Court have abetted Trump’s destruction of our democratic safeguards and norms.

Yet Trump has a significant problem that neither Putin nor Orban faced. When Putin and Orban were consolidating their autocratics, they were genuinely popular. They were perceived by the public as effective and competent leaders.

Just nine months into his presidency, Trump, by contrast, is deeply unpopular. He is increasingly seen as chaotic and inept. As David Frum says, this means that he is in a race against time. Can he consolidate power before he loses his aura of inevitability? Will those who run major institutions – particularly corporate CEOs – understand that we are at a crucial juncture, and that by accommodating Trump they have more to lose than by standing up to him?

To put it bluntly, is the Jimmy Kimmel affair the harbinger of a failed Trumpian putsch?

Krugman goes on to argue that Trump’s declining poll numbers constrain him relative to notable autocrats. Krugman contends that Vladimir Putin, for example, consolidated power partly due to popular support of his economic policies. He points out that while Hungary’s Viktor Orbán was never all that popular, he was popular enough and in the right places.

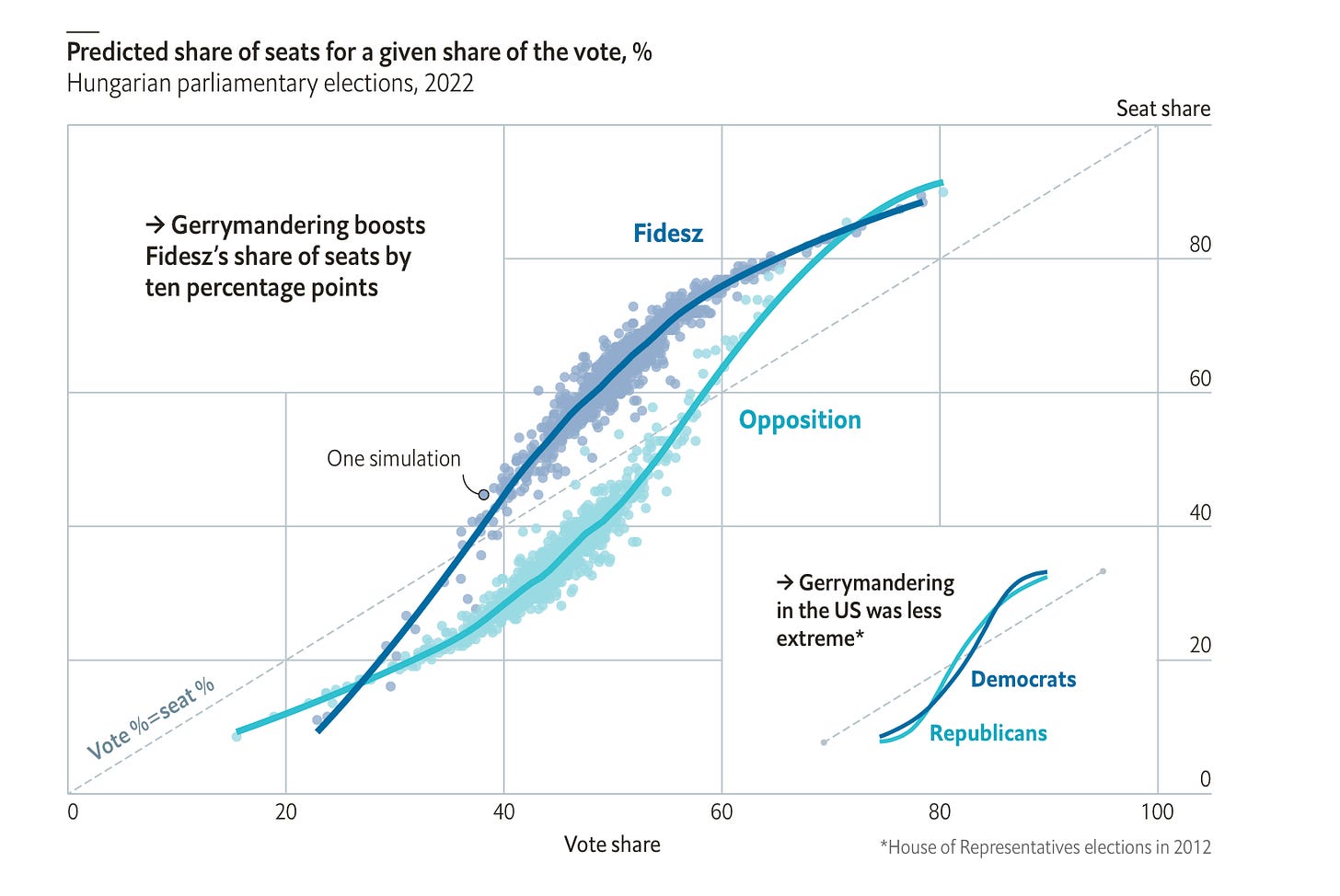

Indeed, Orbán managed to consolidate authority in large part due to his party redrawing electoral boundaries in 2018. I wrote about this for The Economist back in 2022. In that year’s election, Orbán’s party won 68% of the seats in the legislature with just 52.5% of the popular vote.

In late 2022, Orbán’s approval rating was 49%.

Krugman continues:

First, Russia. Putin appears to have been extremely popular in the early 2000s, as he was consolidating power. His net approval — approval minus disapproval — was consistently above 50 percent. […]

Viktor Orban has never been as popular as Putin at his peak. Nonetheless, for most of the 2010s, as he consolidated power, his net approval was strongly positive, often by 10 points or more. Again, the main explanation was probably his perceived economic success. Orban took power at a time when Hungary’s economy was deeply depressed by austerity policies, and was able to preside over a large decline in unemployment. […]

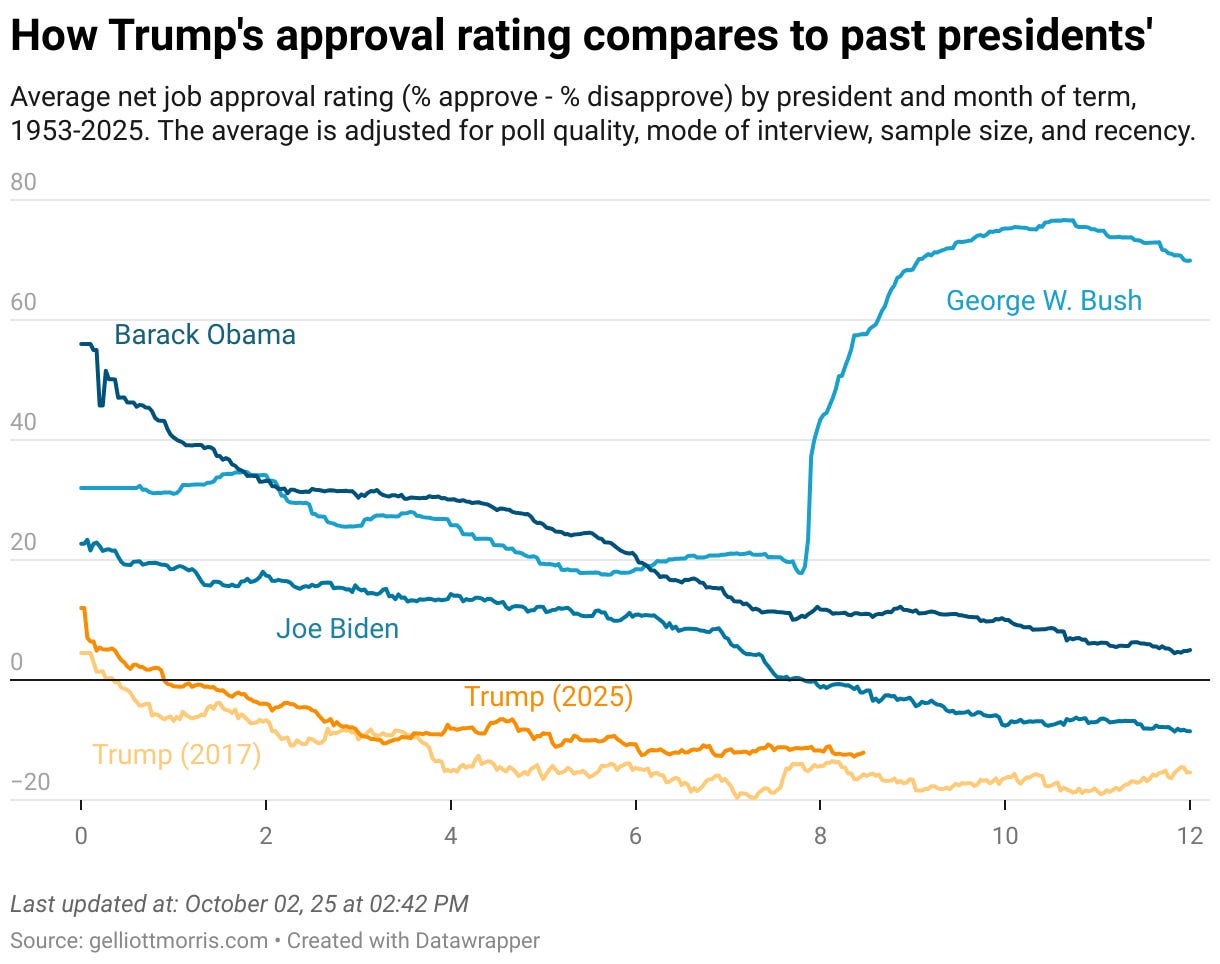

Trump’s net approval, by contrast, turned negative within weeks after taking office and has just continued to fall.

As G. Elliott Morris points out, his position looks even worse when you consider intensity. Almost half the public disapproves “strongly,” twice the share with strong approval.

Some of the public’s disdain for Trump reflects alarm over his assault on democracy, the spectacle of abductions by masked secret police, his attacks on education and public health, his destruction of key agencies like the FBI, and more. Yet, as always, economics plays a key role in Trump’s cratering popularity.

People have not forgotten that Trump made big promises during the campaign: He would end inflation on day one, reduce the price of groceries, and cut electricity prices in half. None of that is remotely happening. Moreover, more economic pain is coming as the full inflationary impact of tariffs and deportations will soon be felt. Not surprisingly, consumer sentiment has plunged. It’s almost as low as it was in the summer of 2022, when Covid-induced supply-chain inflation was at its peak:

These are all good points (and not just because Krugman links to me).

Trump’s presidency has been a case study in how to utilize a narrow popular-vote victory, achieved on the heels of widespread economic dissatisfaction, to consolidate power and shift public policy significantly to the right — far beyond what voters intended.

Yet this shift in government policy to the right has already earned Trump a pronounced backlash in the polls. Trump’s approval rating now is on par with his numbers in 2017, when he earned the achievement of being the most unpopular president ever at this point in his term:

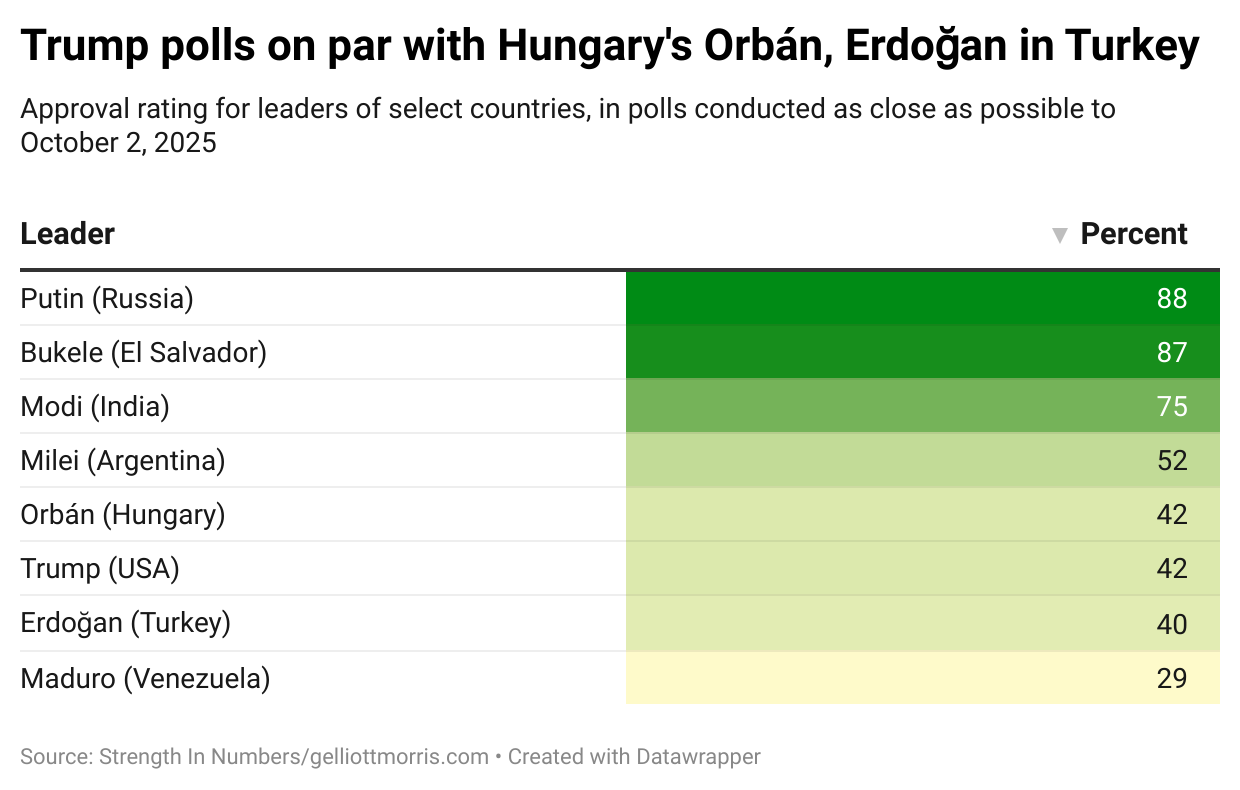

So this all got me wondering: How does Trump’s approval rating compare to notable autocratic leaders today? Sure, Putin was popular when he took power 20-30 years ago, but how do Russians feel about him now? This isn’t quite Krugman’s question (the data he shares is open-and-shut), but if Trump is significantly less popular than, say, Orbán (who, as you will see, is potentially on his way out as prime minister), that tells us something else about the president’s likely future political leverage — as well as America’s comparative openness to autocrats.

Let’s take a look, for today’s Chart of the Week.

Trump is Orbán or Maduro, not Putin

On methods: I began by making a list of the leaders of several “electoral autocracies,” per the definition used by Our World In Data. Then I looked for polls released as close as possible to October 2, 2025. Where I could find multiple surveys released over the last 6 months, I averaged them together. (See the footnotes for my reservations about the data in Russia and, to a lesser extent, El Salvador.1)

According to this data, Trump’s popularity is on par with that of Orbán in Hungary and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey. And eying the range of numbers here — from 29–88% — Trump is less like Putin and more like Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro.

To put it lightly, this is not the portrait of an indomitable president with the public on his side. And the president certainly does not have the “unprecedented mandate” of the people he claimed he had in November 2024.

Yet it’s obvious that Trump sees himself as a leader closer to those popular authoritarians. He claims a highest-ever approval rating (sometimes the imaginary number is as high as 90%), and his speeches to the military (including this week’s) are filled with the kind of grandiose self-praise and demands for personal loyalty that echo what’s common in straight-up dictatorial regimes, not democracies.

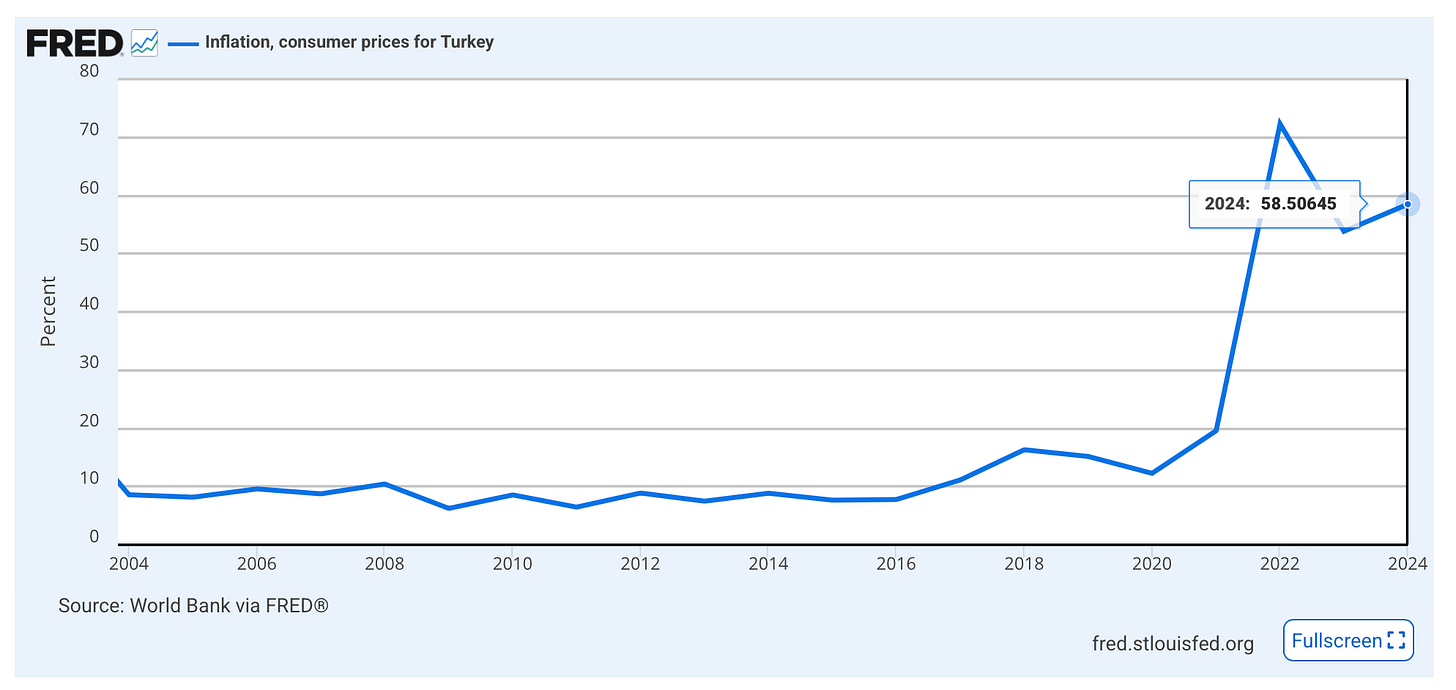

In reality, Trump is barely more popular than Erdoğan, the president of a country that has seen prices go up by 500% over the last 4 years:

Contrary to the folk theory about democratic capture, the lesson from foreign electoral autocracies is that authoritarians need not only institutional control, but also popular legitimacy to make that control durable. Take Putin: He has remained popular (though it’s unclear if current polls can be trusted) despite a decades-long rule plagued by scandal, economic crises, and a long, brutal conflict (now war) against Ukraine. Yes, Maduro “won” the 2024 election in Venezuela, but that’s because he cheated — and the country is now a powder keg. Part of the story is that Venezuelans feel helpless against his rule.

As a closer match to Trump, look to Orbán. After a decade of marginalizing both voters and elites, he may finally be on the way out. An economic crisis has helped push the opposition party to a 15-point lead ahead of next year’s elections. The press and activist groups are starting to put pressure on him for violating EU rights to free expression.

Of course, unpopular autocrats can and do survive. They narrow the information environment by capturing or bullying broadcast outlets (Orbán), flooding the zone with propaganda (Putin), and tilting platforms with regulatory threats. They rewire institutions — packing courts, rewriting electoral rules, and redrawing districts — so that fractured pluralities convert into durable governing majorities. And they splinter or immobilize the opposition: raising legal hurdles for challengers, criminalizing protest, co-opting business and local elites, and using selective repression to raise the personal cost of coordination (see: Trump’s executive order directing government agencies to target, among other groups, the Open Society Foundation).

Our hope should be that this playbook is harder to run in the United States. Federalism creates many veto points on the president (independent state courts, election administrators, and attorneys general), so, in theory, capture must be repeated fifty times, not once. (In reality, partisans are likelier to go along with what the president is saying, so states with Republican trifectas are correlated with each other and not fully independent outcomes. Laws and powers do still differ by state, though, providing some separate state-by-state roadblocks.)

Additionally, independent media in America, and especially an active and heterogeneous digital media ecosystem, complicate full-on information control. Frequent, nationalized elections (House every two years; governors and AGs on staggered clocks) give the opposition recurring focal points to coordinate and punish executive overreach.

None of this makes backsliding impossible (see: the Texas gerrymander), but it lengthens the timeline and increases points of failure for Trump.

Autocrats take over countries when elites — business leaders, media figures, civil society — accommodate rather than resist. This was the story of much of the first six months of Trump’s second term. But, to bring this back to Krugman’s question about Kimmel, when a late-night comedian can successfully defy the president — when that comedian’s parent company feels sufficiently emboldened by public response to defy the president, despite threats of regulatory pressure — his power is in question. The autocratic veneer begins to chip away.

Now, Trump is racing against time, trying to consolidate power before his unpopularity renders his coalition too small to accomplish much, and his demands for fealty ineffective.

Last year, the president claimed an unprecedented mandate. The numbers tell a different story now.

For those who want more, I talked about this (and other subjects) in a podcast with a friend of the site and former Boston Globe columnist Michael Cohen on Monday. The link to our conversation is here.

To be responsible with my journalism here, I should issue two caveats. First, it is not obvious to me, an expert on surveys in democratic societies, how seriously we can take public opinion polls collected in autocratic regimes. For one thing, high-profile public opposition to government is effectively illegal in Russia, where elections are no longer free or fair, and opposition lands you dead or in prison. It is unclear who would tell a pollster, even an independent one, that they disapproved of Putin if he could throw them in jail for it. Where public opinion is a concept fully or partially divorced from the public’s private opinions, polls are less useful.

Second, the veracity of the polls themselves varies widely by country. Where I found methodologies for these surveys, things looked to be in order, but I am not an expert on the weighting methodology you should use in India or the different states of Brazil.

My opinion is that, when imperfect data are all we have, the best path forward is to share the caveats and move on. The consensus is that polls in Russia probably exaggerate “true” support for Putin. But what that means in practice is hard to get one’s head around.

Trump's authoritarian push feels a little like Putin's Ukraine push - lots of ground was gained right at the beginning with little resistance, and now we're in trench warfare well within the borders. One wonders how things might have been different if the establishment had chosen to treat November 2024 as the clear but narrow loss it was for the Left, rather than as the frequently-cited "shellacking" or "crushing defeat" the media chose to portray. If Trump has been accurately portrayed as barely scratching out a victory in a very favorable environment, perhaps fewer institutions would have capitulated in the first few months.

My major issue with all of the mainstream media coverage has been the sane washing of Trump. I canceled my decades long NYT subscription because of their blatant failure to accurately report what Trump was actually saying in his rallies. As his mental decline only worsens it gets harder for the press to sane wash his gibberish and his support will erode into the 30's. By the way I'm really glad Paul Krugman sent me your way! Keep up the good work.