Presidents' Day Links | February 12-18, 2023 | Asymmetric polarization; "Rich Democrats, Poor Republicans"; and Dissatisfaction with gun, abortion, family policies

George Washington never got to join the Congressional Dads Caucus

Happy Monday, subscribers.

This is a special Presidents’ Day edition of my weekly roundup of articles/books/charts/media etc. that I think are interesting and worth discussing.

This week, we review some recently published newspaper and academic articles and look at dads in Congress.

1. Polarization has affected the parties differently

The Washington Post’s Philip Bump wrote an interesting piece last week looking at how members of Congress have polarized over time. He wondered whether it was historically weird or not for members of Congress that won by small margins (such as Lauren Boebert) and large margins (Marjorie Taylor Greene) to be so ideologically similar. He looked at every House race since 1976 and plotted a House representative’s margin of victory against their ideology score as measured by DW-NOMINATE (see discussion about these scores here). So here are two plots, showing these relationships in 1976 and 2022:

Notice that there is generally a linear trend for Democrats—the group of people in the bottom half of the chart. They get more liberal as their margin of victory grows. Republicans, on the other hand, exist in a blob; there is no relationship between the margin of victory and the degree of “conservatism”, at least as measured by roll-call votes (again, see discussion here).

Another way to look at this (and kudos to Bump for the great chart) is to see that districts that give Democrats and Republicans the same margins have polarized unequally over time. For Democrats, margins of victory have grown slightly in most districts, but close seats have not elected new members that are any more liberal than members who came before. On the Republican side of the aisle, however, red seats have gotten significantly redder, and members are much more conservative:

But Bump leaves an important question open: why has there been polarization within districts, anyway? That reminded me of a recent paper by UCLA political scientists Jeffrey Lewis and Luke Sonnet. They train a new version of DW-NOMINATE (called PSDW-NOMINATE) which allows for individual Congresspeople to have ideological scores that change over time, something the oft-cited algorithm does not. And this lets them answer the question of whether members are getting more ideologically extreme as they stay in Congress, or whether the members that replace them are more extreme, thus driving aggregate measures of polarization higher.

The authors find that polarization, especially among Republican members of Congress, has been caused mostly by the latter. In fact, from 2009 to 2018 Lewis and Sonnet find that Democratic incumbents did not get any more liberal over time. Replacement members, on the other hand, were 7% more liberal. Republican replacements got much more conservative, while incumbents, too, became modestly more so. Political scientists have many explanations for this phenomenon, including downward pressures on mass attitudes from the likes of party leaders and Fox News, and about social sorting in more demographically homogenous districts.

2. Rich Democrats, Poor Republicans

In 2007 political scientists Andrew Gelman, Boris Shor, Joseph Bafumi and David Park published a paper in the Quarterly Journal of Political Science titled “Rich State, Poor State, Red State, Blue State: What’s the Matter with Connecticut.” The paper detailed a paradox of voting behavior in America: why are rich states more Democratic, but rich voters vote Republican? The answer, expanded later into a book bearing the same name as the article, is summed up elegantly in the following chart. In poor states, the rich vote much more for Republicans than the poor do; In rich states, though, there is less of a relationship between the two:

One conclusion of the book? Per the New Yorker: “Of the popular image of affluent, urban, latte-drinking Democrats, Gelman pointedly notes that the demographic is most common in ‘precisely those states where national journalists are likely to live.’” Elsewhere, the finding implies, the rich are Republicans; lawyers, owners of car dealerships and small businesses, ranchers, etc.

That, however, was in 2007. Today is 2023 and things have changed. A new report from Lee Drutman and Oscar Pocasangre of the New America foundation finds that most Democrats come from rich Congressional districts, and Republicans the poorest.

Drutman says:

Three quarters - 75 percent — of Republicans in Congress represent districts that are less wealthy than the average district. Among Democrats, a slight majority of the congressional delegation comes from wealthier than average districts.

Likewise, two-thirds of more affluent districts (67 percent) sent a Democrat to Congress in 2022, while 63 percent of less affluent districts sent a Republican to Congress in 2022.

That certainly is a dramatic undoing of Gelman et al’s Red State, Blue State.

Joining the chorus of researchers writing on this topic, Yale Political Science PhD student Sam Zacher in a new paper looks at survey data and finds similar increases in wealth polarization over time.

As recently as 2012, Zacher finds, voters in the bottom third of the income distribution gave Democrats a vote share that was 15 percentage points higher than voters in the top third by income. But now they are separated by just 5%, with poor whites voting less for democrats than rich whites:

This is a dramatic reversal of previous patterns. While there used to be a linear relationship between wealth and voting Republican, there is now a U-shape; The poor, in other words, are roughly as Democratic as ever. But the rich are much, much more Democratic than they ever have been:

The increase correlates strongly with education polarization, according to Zacher. Voters who do not have college degrees but live in households making more than $150,000 per year have become modestly more Republican-leaning than the average voter since 2012. Well-educated, wealthy voters, on the other hand, have become nearly 20 points more Democratic. These patterns hold if you control for education, race, and gender.

Surely polarization on social issues has a role to play, too. 2016 and 2020 were the standout years for wealth polarization, according to Zacher.

This is likely to have profound consequences for the politics of wealth distribution in America. One of the groups of people most favoring the party of a large social safety net are rich whites (following, by a large margin, non-wealthy non-whites). And while this new group of affluent Democratic voters is very multiracial and college-educated, the non-college-educated affluent have also become more Democratic. At the same time, Democrats in Washington have become more supportive of large social-spending programs—see, eg, Biden’s Build Back Better, Infrastructure Act, the IRA and the American Rescue Plan.

But a coalition of wealthy and poor (non-white) voters may be hard to mobilize around more “radical” proposals. An agenda of workers’ rights and true wealth redistribution will likely become an increasingly hard battle, where Democrats would prefer to do things like raising the SALT deduction and protecting the home mortgage interest deduction.

I’m sure there’s lots more to say about the Brahminization of The Movement.

3. Satisfaction with key policies at an all-time low

Finally, here is a collection of links about low satisfaction with crucial government issue areas:

Gallup: “Majority in U.S. Still Say Gov't Should Ensure Healthcare”

Gallup: “Dissatisfaction With U.S. Abortion Policy Hits Another High”

Even more Gallup: “Dissatisfaction With U.S. Gun Laws Hits New High”

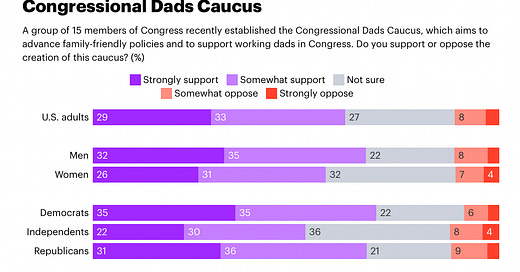

The last link includes this absolutely amazing chart about something called the “Congressional Dads Caucus”:

And here is a picture of the Congressman who started the Caucus, for all who love a good baby björn.

That’s it for this weekly edition of my top links. Thanks for reading and being part of the community that supports this newsletter.

If you saw something new or insightful, consider sending a free trial of my newsletter to a friend you think will enjoy it — or send them a year-long gift subscription.

Elliott