The Strategist’s Fallacy in American politics

The average American voter does not think about politics the way elite strategists and pundits do

I was going to write today’s post about social media, attention, and politics — specifically, why I think the increasing use of AI algorithmic recommenders on the major platforms, including TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and soon, Twitter, makes them less useful for political analysts, journalists, and users alike, and why they’re bound to further increase polarization and destabilize politics. As a former Twitter addict and data journalist, I feel I have something useful to say on the subject.

Then, when I was writing, someone sent me a new report about Democrats’ losses in 2024, written by the centrist Democratic group WelcomePAC, that consumed my attention for the rest of the day (go figure). So I will return to social media and attention another time.

The report, which deserves credit for its breadth of data and the depth of its empirical investigation (I reckon it was more work than some PhD dissertations), makes the argument that Democrats lost the presidency in 2024 because they embraced too many progressive policy ideas. The authors conclude that for 2028:

Democrats should pick a nominee who understands what it takes to win elections in difficult terrain—and is willing to run on positions that majorities of Americans support, even if this sometimes requires breaking with the unpopular demands of progressive advocacy organizations, corporate interests, or the Democratic donor class.

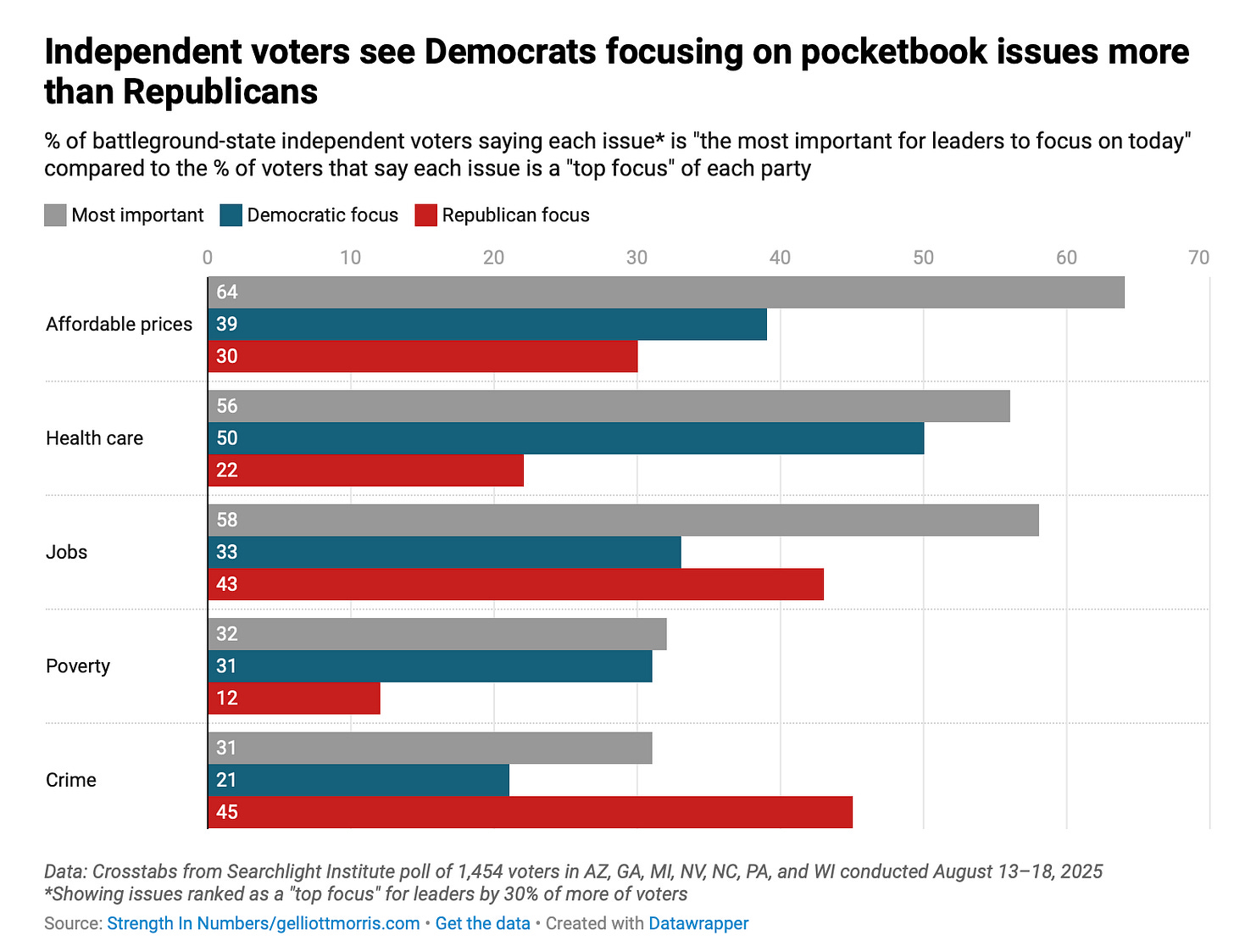

I have some criticisms of the way the authors come to their conclusions. For one thing, while making prescriptions for the future of the party, the authors are surprisingly ignorant of current data that shows the Democrats rebounding with voters who care about the economy, and Republicans doing as poorly as or worse than Democrats on issue focus. The report also spends little time discussing the role of inflation in Kamala Harris’s loss in 2024, and frames the economy as an exclusively Democrat vs Republican problem instead of acknowledging an incumbent vs opposition dynamic at play last year — a big mistake that I have covered before.

The group also reads too much into unadjusted, uncertain differences in the electoral performance of “moderate” and “progressive” congressional candidates — the same mistakes plenty of other people are making recently. The issue is not just that these patterns are highly subject to the way a person defines “moderate” or “progressive,” but that past data is not a good predictor of future results. The individual skill of a member of Congress, in my research, changes significantly from cycle to cycle (in the WelcomePAC’s own data, overperformance by a candidate in one year predicts just 25% of future overperformance by that candidate. Ideally, that number would be 100%50% (see footnote for correction1).

But my biggest problem with the report is with the conclusion itself. The report suffers from something I’m going to call the “Strategist’s Fallacy” in politics — the tendency for campaign consultants and political strategists, especially on the Democratic side (where quantitative analysts are overwhelmingly focused on policy positions and ideological point-positions), to map their mental model of how they make political decisions onto voters. They implicitly assume all voters make choices and select candidates the same way elites do. This is wrong for several reasons, which I will explain.

The report also uses some pretty comically inaccurate data to make its case — for example, saying it was part of the Democratic policy agenda in 2024 to abolish prisons, make DC a state, and pass Medicare for All. I touch on this after diving deeper into the Strategist’s Fallacy:

The Strategist’s Fallacy in Democratic Party politics

The Strategist’s Fallacy, simply put, is the incorrect belief that voters think like strategists — i.e., that they hold concrete issue positions and ideological labels and match them up to candidates, like a customer picking an entree off a dinner menu — so the way to win is for a candidate to tweak their individual positions on policy. This mental model does not hold in reality, leading individuals to provide poor assessments of voters’ decisions and organizations to give candidates poor advice.

The rest of this article is paywalled for paying members of Strength In Numbers. I like to keep a good amount of content on this newsletter free to read, but I also have to balance my commitment to the business and premium readers. If you want to read the rest, become a paying subscriber to Strength In Numbers today and unlock this and other premium analyses and data on U.S. politics and elections.