The Democrats' problem in the Senate is not progressives | Weekly roundup for November 2, 2025

Their big problem is not a lack of moderates, it's nationalization of party brands. And: A new era for the exit poll; The end game of partisan gerrymandering; and how Substack's AI works. + more!

Dear readers,

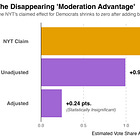

Context for this week’s lead data story: In recent months, I’ve found myself arguing that ideological moderation is a false promise to fix the Democrats’ electoral problems. Ideological moderation has small effects on elections that would not have been enough to flip the outcome in the House or Senate to Democrats in 2024, and proponents of the strategy base their conclusions on faulty data analysis, a deep-seated Strategist’s Fallacy about voter psychology, or both. I have said moderation is akin to “putting a band-aid on a bullet hole.”

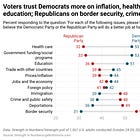

But I do not deny the Democratic Party has problems. Working class voters, the constituency the party says it is advocating for, say the party is out of touch and doesn’t care about them. This matters particularly in the Senate, where rural, white, working-class voters are overrepresented. So, if moderation isn’t enough to fix that problem, what is?

My case, which I am developing for a longer essay, is that you have to think bigger, be creative, and change what it means to be a Democrat — particularly in rural areas. And that’s not an ideology problem, but a culture problem. It’s a party services and connection problem. One look at historical electoral data published this week agrees with my general premise. It argues that seeking the middle misses the forest for the trees.

On deck this week: It’s election time! In place of the usual Tuesday premium post, I’m joining a live election-night conversation hosted by my friends at The Downballot. You can tune in at 7:00 PM ET via the Substack app or at the Strength In Numbers website. I think I’ll have enough time to develop county-level benchmarks for the races for governor in New Jersey and Virginia by then, which will help determine which candidates are leading early in the night. That’s what I did for our last election stream, and people seemed to find it valuable.

I have several non-newsletter commitments this week, including two lectures on the election results, so posting will be sparse mid-week. By Friday, I should have a good post-election #take penned, and I’ll have a recorded conversation with Paul Krugman about the election online on Saturday. What I’ll be looking for is information about how low- and medium-turnout-propensity voters have shifted during the second Trump term (we know that high-propensity voters are moving left from special elections), and clues about how the Democrats’ affordability agenda is (or isn’t?) resonating with voters.

The big problem for Democrats is the nationalization of elections, not “woke” ideas

This week, several political scientists and statisticians I respect published rebuttals to the claim that moving right on issue positions will help Democrats win future elections. These articles are linked in the “more numbers!” section below.

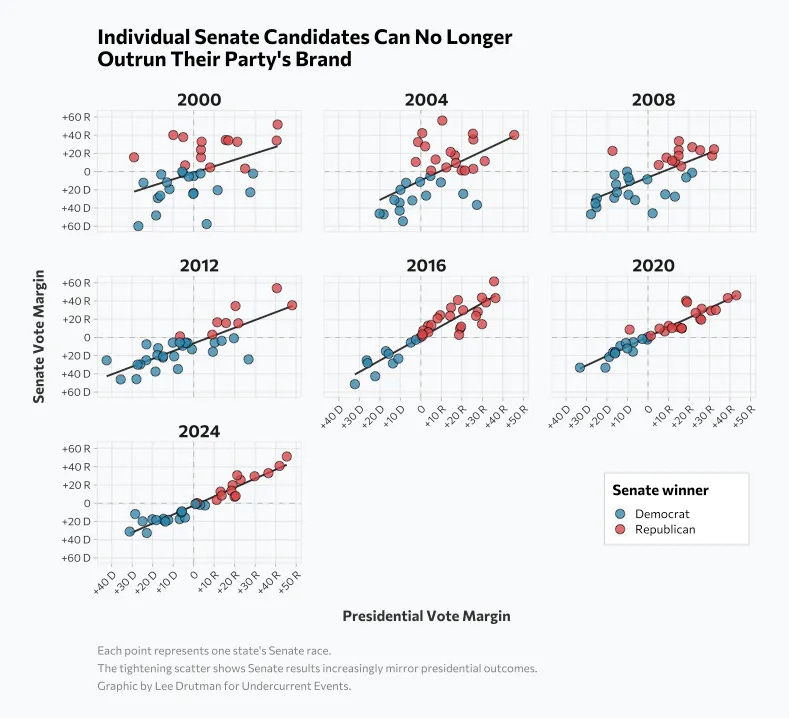

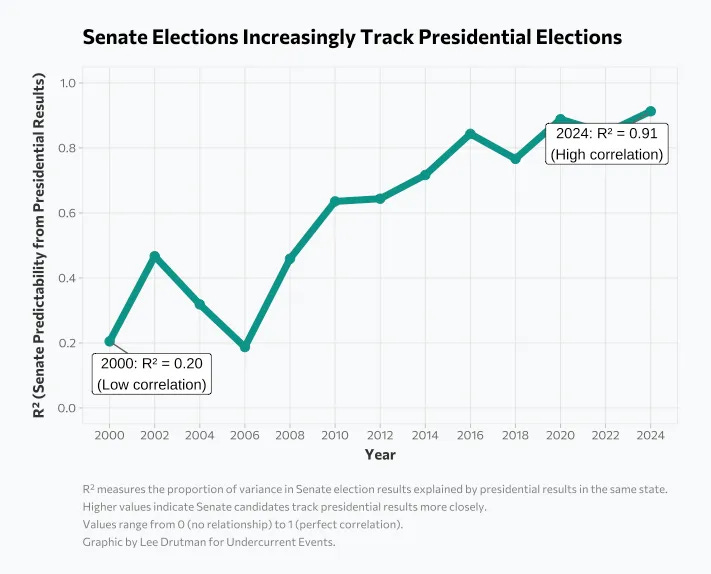

One of these analyses stood out to me: A response by Lee Drutman, a political scientist and Senior Fellow at the New America Foundation, titled “The moderation debate fiddles with 2% while democracy’s dimensionality collapses.” Lee observes, with implications particularly for the Senate, that the big reason Democrats have a harder time winning in redder seats now (versus 25 years ago) is that voters have become much likelier to vote for down-ballot candidates that match the party of their preferred presidential candidate

In other words, the correlation between presidential and Senate outcomes has risen dramatically over the last 25 years — particularly after Barack Obama was elected in 2008:

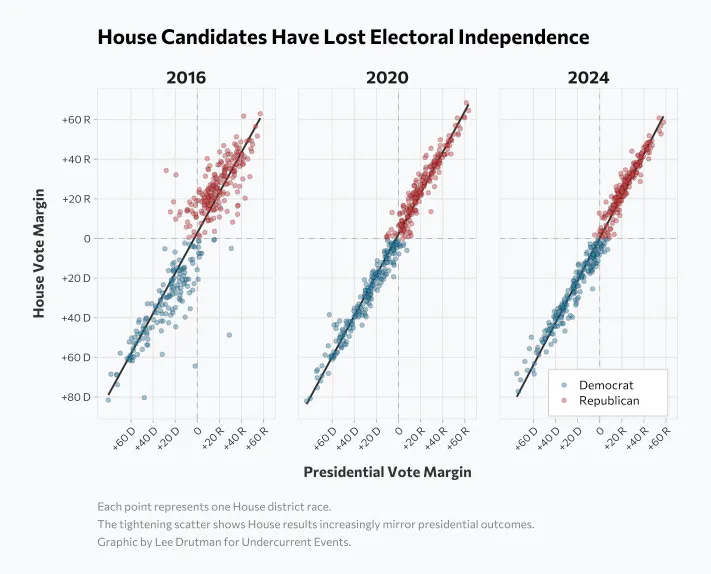

And this is all true at the House level, too:

I like Drutman’s piece because it takes the long view of how Democrats ended up where they are, and why recent debates about the overperformance of moderate Democratic candidates fall short. We are squabbling over how to juice 1 percentage point of vote margin out of an electorate, diagnosing these small differences as the big story of politics today, when the real question for the party is why the average difference between vote margins for presidential and congressional candidates has decreased by 80% over the last 25 years. The big question for Democrats in trying to win the Senate is how candidates can differentiate themselves from the national party brand.

The folks on the “Democrats need to moderate their issue positions” side of this debate imply the reason Democratic candidates such as Jon Tester (MT) and Sherrod Brown (OH) lost in 2024 is because they were too progressive on “social issues” like gun control, abortion, etc. However, this narrow diagnosis contrasts with the broader view of politics, which suggests that individuals who consider themselves Republicans have become less likely to vote for any candidate without an “R” next to their name. It’s not just about ideology and progressive activists or land acknowledgments.

In other words, we are in a world where strategists are obsessed with marginal vote gains for ideological moderation because much larger forces have decreased Democratic performance in red states. But few activists are thinking about how to detach congressional from presidential voting at the individual, psychological level.

We know that the problem for Democrats in the Senate is not ideological extremism because the nationalization of elections pre-dates the current ideological conflict in the Democratic Party. Before Tester and Brown lost in 2024, you had Joe Donnelly (IN), Claire McCaskill (MO), and Heidi Heitkamp (ND) losing in 2018. That was before “woke” was even a term in our politics. And in 2012, Democrats lost a 2-term incumbent Senator from Nebraska, Ben Nelson, when he decided he couldn’t win against the Republican nominee. Nelson was the most conservative Democrat in the chamber. Even with his conservative voting record, he couldn’t overcome Nebraskans’ affective polarization against Democrats, regardless of candidates’ views. And again: this was before the party was perceived as a liberal, progressive party.

Moreover, nationalization is not dangerous for Democrats because of inherently ideological mechanisms, and in fact can hurt progressives too. Consider that moving every Democratic Party candidate to the exact middle of the left-right ideological spectrum would marginalize progressives, who the Democratic Party cannot afford to lose. An urban party in a system with geography-based representation is disadvantaged by a national brand, whether that brand is left- or right-leaning, because its voters are split across electoral boundaries. That’s it.

This was not a problem for Democrats 60 years ago. Previously in American politics, there was much more geographic variation in what the parties meant to voters. Being a “Democrat” from Montana could mean something different from being a Democrat from New York City. This allowed candidates to distance themselves from the national party brand and from the perceived cultural sins of candidates in faraway places that shared the same party label. As regional variation in party labels has fallen, this has seriously disadvantaged the party associated with urban voters.

Call it whatever you want — polarization, nationalization, “Balkanization,” factionalism, etc. It is simply true empirically that individuals moderating their issue positions, but sticking within the same party label, is not a solution to that problem. As I wrote on Tuesday, this solution is analogous to putting a band-aid over a bullet hole. The root of the problem is not issue positions; it’s something much bigger.

To be clear, this isn’t just a problem for the Democrats — it’s a problem for democracy. As nationalization has decreased split-ticket voting, it has increased the number of safe seats in both the House and Senate. This decline in competition is bad for a lot of reasons: it limits accountability for poor performance of the government, leads to the entrenchment of members who are otherwise out of touch, and reduces incentives for parties to appeal to a broader range of voters. When politicians feel secure in safe seats, they have little reason to iterate upon their positions, listen to dissenting voices, or invest in genuine engagement with their constituents. Over time, this can deepen polarization, weaken democratic responsiveness, and erode public trust in the political system itself.

So, back to the piece: Drutman’s idea to counter nationalization is to allow each candidate on a ballot to be nominated by multiple parties — something called “fusion voting” in the electoral reform space. Drutman has done the math and finds that allowing fusion voting would increase the number of competitive seats in the House and Senate. This is because it allows candidates to break from the mold of the major parties and still get placed on general-election ballots. You can be both a Democrat and a Working Party candidate, or a Republican and a Common Sense candidate (or just a Common Sense candidate). The goal is to increase the supply of parties, and get voters out of their habit of thinking of politics as just Democrat vs Republican.

Here’s another example illustrating the shortcomings of the moderation thesis: An independent candidate named Dan Osborn ran for Senate against incumbent Republican Deb Fischer in Nebraska in 2024. He came within 5 points of winning, in a state that voted for Trump by 20 points. He ran on an anti-swamp, pro-Trump, pro-border wall agenda.

Setting aside that a Democrat would never have been nominated with that agenda, I am confident that a Democrat would not have come as close as Osborn even if they took those same issue positions. That’s because Republican voters attach stereotypes and baggage to Democratic candidates simply because of their party label.

If you’re a Democrat interested in breaking the Republican stranglehold on the Senate, the way you do that is to decrease the number of Republican Senators in the Senate. You can try to accomplish that by running a bunch of pro-Trump “Democrats” in red states like Nebraska. Or you can support institutional reforms to increase the likelihood that the anti-Democrat voters of Nebraska elect someone from a party other than the Republican Party.

Here’s another piece from Lee on fusion voting.

What you missed at Strength In Numbers

Here’s everything I posted on this newsletter over the last seven days:

Friday’s post covered the results of our new national poll, the final one before voters in NJ, VA, NYC, CA, and elsewhere vote in state and local elections on Tuesday:

My premium essay on something I’m calling The Strategist’s Fallacy — a tendency for quant (mostly Democratic) political strategists to project their personal mental model of voting behavior onto the average voter:

And my response to a big essay from The New York Times Editorial Board that argued Democrats must move to the center to win future elections:

These days, I am also posting a lot more medium length notes on the Substack Notes tab in the Substack app. If you’re hungry for more Numbers, you can find my musings between essays there.

As you’re thinking about the media diet you want to create for next year’s midterms, consider a paid subscription to Strength In Numbers. Members get extra premium posts at least once a week (and, lately, more like 2-3x a week), an early look at any data products I’m developing, access to a private Discord server just for paid members, and more. Paying members also support all the work that goes on behind the scenes to put together the SIN/Verasight poll, my state and congressional district MRP models, and all the other analyses that power my journalism.

Even more numbers!

Links to other articles in the political data space I discovered over the last week:

For more on how the pro-moderation crowd is exaggerating their claims, read:

Philip Bump: “Politics is more than temperature-taking”

Jonathan Bernstein: “A Mantra for the Democrats”

Andrew Gelman: “The WAR war and the electoral benefits of running more moderate candidates for political office”

The Pew Research Center shows that Americans view both parties as extreme and unethical, not just the Democrats

Election poll news! Years ago, Fox News and the Associated Press split themselves off from the collective of news networks (called the National Election Pool) that funded the traditional Exit Poll and supplied the election returns you’ve probably seen on television news outlets. Well, last month, the company that conducted the Exit Poll and supplied those returns was acquired by SSRS, a pollster and large research firm. Now, the gang is getting back together, combining the insight from the VoteCast survey from Fox/AP with Edison’s traditional Exit Poll. The first test of their new methodology will be this week’s elections!

Nate Cohn shows what a world of partisan ultra-gerrymandering will look like in states such as Texas and California. Every more reason to support anti-gerrymandering reforms, which are popular with a majority of voters.

The head of recommendations at Substack tells us how their timeline works in an interesting (nerdy) read that’s part history and part Substack.

Computational social scientist Petter Törnberg shows us the political leanings of users of major social networks like Twitter, Instagram, and BlueSky.

And Philip Bump has a great visual network analysis of the people involved in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol in his newsletter, How To Read This Chart.

Polling update

The Strength In Numbers polling averages have moved to a new webpage at fiftyplusone.news, a website purely for poll-tracking that I’ve set up with my friends. Some averages, like my average of Trump’s issue approval, remain on the data portal.

Trump’s approval is -14, a new low.

The generic ballot is D+3, after briefly hitting D+4 this week.

The Democratic candidate is up 11 in the Virginia governor’s race.

The New Jersey governor election is D+7.

That’s it for your major political data stories this week.

Got more for next week? Email your links or add to the comments below!

Have a nice week,

Elliott

To your point on nationalization, research on the impact of the decline of local news parallels your findings. From The state of local news and why it matters from the American Journalism Project:

"Research shows that the loss of local news is having an insidious effect on our democracy — contributing to polarization, decrease in voting, and government accountability. Local news is an essential lever to a healthy democracy; it helps communities understand what’s at stake in local elections, equips them to get involved in the political process by voting, contacting officials and running for office, reduces political polarization, and holds public officials accountable."

https://www.theajp.org/news-insights/the-state-of-local-news-and-why-it-matters/

So one clue to remedying the move to nationalization is to increase differentiation that can come through strengthening local news.

As someone running for Congress now, a big part of the nationalization problem is fundraising. If candidates had to prioritize raising from their own communities, instead of tapping the same lists of national donors, their messaging wouldn't be so homogenous (aiming at the lowest common denominator of the list) and/or over-the-top (competing for attention with every candidate from around the country). My first policy roll-out was for federal public financing based on the system we have in CT — small dollar donations from within the district trigger larger public grants. I think it would help with this unique phenomena.

It would also remove barriers to entry for untraditional candidates without access to national fundraising connections or personal wealth, making it easier to build the "big tent" I keep hearing about.

Of course, that won't end the incentive to caricature the opposing party (which the right has done to extreme success), but I do think that caricaturization becomes less effective when candidates have stronger relationships with their voters.

If anyone's interested: https://voteforjillian.com/issues